Sunday, January 31, 2021

All is bright

Saturday, January 30, 2021

Rite and Wrong

In my last post, I showcased a video in which Freddie Mercury's We are the champions melody is repurposed in the mold of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring bassoon solo.

- The Rite of Appalachian Spring

- The Reich of Spring

- The Reich of Spring in San Francisco

- The Rite of J. Peterman

- The Rite of Springfield

- The Rite of Springtone

- The Riteroica of Spring

- The Rite in Black and White

- Rites of Spring

- The Wiggles of Spring

- The Rose of Spring

- The Rite Way to Google Stravinsky

- The Rightness of the Rite

- The Rite Reversed

- Mr. Stravinsky's Random Accent Generator ~ Version 2.0

- It Rite As Well Be Spring

- The Rite of Spring Sonata

- Hidden Rites

Thursday, January 28, 2021

Hidden Rites

As you can see/hear, I decided to string together a series of samples, each focused only on the first eight notes of Stravinsky's melody:

- In the first two examples, we hear Stravinsky's original key (starting on a C) which means poor Freddie Mercury gets bumped up a 5th. (At least I didn't make him go as far as "keep on fighting," which would take him up another 5th!)

- The first example has Mercury singing his original melody.

- In the second example, his melody is adjusted (following the small alternate notes shown) to fit more closely with Stravinsky's bassoon.

- In the third and fourth examples, we hear the same thing as the first two except with everything transposed down to the original key in which Mercury was singing.

- Finally, we hear the original Stravinsky bassoon by itself, following by Fake Freddy singing the bassoon melody (-ish) alone. If this had all worked out like I hoped, hearing Fake Freddy at the end should sound like he's straight up singing Stravinsky.

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

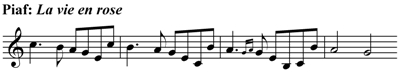

What's fascinating is that there are far fewer shared pitches between these melodies which nonetheless DO call out to each other (at least in my mind). The first phrase of La vie en rose comes to rest on B, not A, for example. However, the French tune has a rhythmic shape that is closer to Stravinsky: a long note, some fast notes that outline a triad and end with a leap up, followed by a step down to another long note. And really that's it. Note that like We are the champions, La vie en rose is in a clearly major key, so it's not a harmonic thing.

Maybe it's just the French influence in Stravinsky and La vie. Here's Edith Piaf's singing adjusted up to start on the same note as Stravinsky.

Back in 2007, I wrote about these melodies:

They also both have Parisian associations, and the sultry high register of the bassoon is at least as distinctive as Edith Piaf's freaky timbre....I wasn't able to Google much mention of this pairing, but I'm intrigued to see that some Peter Schickele wannabe named Ernest Acher recorded a "Rite of the Rose," along with other such mashups in an album entitled "Mischief with Mozart: Classical Combat with the Classics." I haven't been able to find an audio sample, but it's not hard to imagine.

First of all, an important 2021 update: I found that Rite of the Rose recording! You can hear it here. It's fun, staying mostly in a Rite of Spring vein, with the bassoon melody eventually veering into La vie en rose territory. The French tune actually takes over briefly around 2:25, but not for that long. You can also hear the musical humorist Hyung-ki Joo doing a lighthearted little mashup in the Paris airport here - for some reason, he ends with music from Stravinsky's Petrouchka. Anyway, I'm not the only one to make this connection.

But ultimately, I think it's the suave, sensuous, flowing quality that unites The Rite of Spring with La vie en rose and separates both from the more muscular, insistent We are the champions. And it's a reminder that, though pitch is obviously important in defining a melodic identity, shape and gesture may matter just as much. Your mileage may vary, but when I hear Stravinsky, I think C'est la vie (en rose).

P.S. The Rite of Spring remains the topic about which I've written the most. Here's a post linking to many such other posts.

Monday, January 25, 2021

Humming Along

Last week, I wrote about my solo piano recording of an a cappella choral work - an a cappella work about a blue bird. That call-back to my "Songs Without Singers" series from the early years of MMmusing gave me the idea of re-visiting and updating all these recordings for our new multimedia world. Once again a bird is the subject of today's song, though once again, all the singing will come from the hammered strings of a piano. And like Stanford's The Blue Bird, this song also makes notable use of the minor seventh chord.

Back in 2008, when I recorded six songs without anyone singing along, YouTube was in its infancy, and so I just posted mp3 audio recordings in the clunky way Blogger allowed. As my YouTube channel has grown, I find satisfaction in archiving such recordings on video with my favorite kind of visual to accompany: THE SCORE. I've written countless times about how much I love watching music notation float by and how much I love creating notation for that and other purposes, so my goal is to get these old recordings scrolling onto YouTube and perhaps out to more listeners.

Ernest Chausson is a bit better-known than Charles Stanford, and it wouldn't be fair to call either a one-hit-wonder. But with both composers, it's a small-scale song inspired by humble poetry about a bird which has stolen my heart. I described Stanford's The Blue Bird, which clocked in at exactly four minutes on video, as "perfect," and the same word applies perfectly to Chausson's Le colibri, which curiously enough times out at exactly three minutes. (Both videos include some silent seconds devoted to title, but it was a happy accident that each ended up with the second hand pointing straight up.)

Chausson's song is about a hummingbird; but it's really about something else, which perhaps explains why Chausson's writing is not at all quick or neurotic, but rather leisurely, lush, and sensuous. You can read a translation of Leconte de Lisle's sonnet here. My French is much too bad for me to judge the poetry on its own merits, and I'll admit that I loved this song for years (it's often assigned to voice students) without worrying what any of the words even meant, other than thinking the music doesn't sound very hummingbird-like.

My singer-free recording dates from an early morning impromptu session in my office thirteen years ago, but I've spent hours this past weekend making an elegant scrolling score and thinking about why this music is so magical. First, I'll admit that I was going for a kind of 19th century French look here and thus chose some fonts that are a little more stylized than I'd usually consider ideal. I even kept the unbeamed 8th notes in the vocal line, though I generally much prefer the more modern convention to beam to the meter rather than the syllable. This results in a lot of looping flagged notes, but the rhythms and textures are simple enough, and this helps to emphasize how syllabic the setting is. (Even the slightly out-of-tune and fairly humble piano sounds right here for this intimate music.) It's hard to express how much I love watching these notes moves across the screen.

Something I'd forgotten about this song is that it's in 5/4 time, a pretty unusual choice for 1882, if not quite as unusual as the 5/8 of the much earlier Reicha fugue I wrote about last year. In this case, the quintuple meter functions less to create obvious asymmetry than to give the phrases breathing room. Notice how the wide-ranging arpeggios in the richly scored introduction further distort the sense of a strong pulse; that quarter rest in m.2 could be heard as nothing more than an indulgent lift. Even the five repeated A-flats that lead to the singer's entrance are just lonely reverberating quarter notes with no other elements to define the metrical context. Back when I was playing this accompaniment regularly, I can remember counting those notes carefully, and also being prepared for the singer to come in AT ANY TIME.Chausson ushers us right away into a dreamy soundscape with an A-flat major chord that rolls all the way up to an F, a pitch which doesn't belong in the chord. Although one could analyze it as an inverted minor seventh chord (and we'll get to the minor seventh soon), the steady A-flat in the bass through these four bars makes it more logical and meaningful to hear that F as an expressive over-reach - a non-harmonic tone a step above the chord tone E-flat. And now I'm going to avoid describing every single beautifully chosen note in this introduction, but there's a remarkable range of color and shape as falling melodic gestures are suspended over exotic harmonies.

Down to the flower he flies, alights from above,and from the rosy cup drinks so much love

"From the rosy cup," we are told, the hummingbird "drinks so much love." So much love that...? Well, if you check out the waveform above, you can see the music dips down to silence. And this is the most inspired moment. After the expectant V7 chord and the silence, the vocalist sings a simple V-I motion of A-flat to D-flat; except, instead of D-flat in the left hand, we end up with...a heartrending minor seventh chord on E-flat.

In fact, it's even more special than that because at first we only hear a single low E-flat against the vocal D-flat, with the rich harmony filling in a beat later. Chausson must've loved this moment as much as I do because the piano just keeps gently pulsing that chord pianissimo for what seems like forever. Just as Stanford demonstrates throughout The Blue Bird, the minor seventh chord is perfect for stopping time. And what is the text here? That vocal A-flat to D-flat is sung to the words "Qu'il meurt," which means: "that he dies." The entire tercet translates as:

Down to the flower he flies, alights from above,

and from the rosy cup drinks so much love

that he dies, not knowing if he could drink it dry.

Now, at m.33, the vocal part returns to its opening melody in D-flat for the final tercet. Having reached the high F seven times previously, the voice finally ascends a half-step higher to begin the closing line of the poem, singing "du premier baiser" ("from that first kiss") just as that high G-flat is touched at last. (The harmony under that first kiss? A minor seventh chord.)

Notice that the subject has shifted from the hummingbird to something more personal, and we can imagine other meanings for the death caused by drinking so much love from the flower.

Even so, my darling, on your pure lips

my soul and senses would have wished to die

from that first kiss that perfumed it.

Having begun the song with arpeggiated chords, the piano concludes with three rolls, all the way up to a beautiful kiss-like ping as the final sound.

So, yeah, that's a lot of words about three minutes of music, but it's such exquisite music. There's also something very satisfying about the tactile experience of playing this piano part, right from that opening sweep, and looping in the melody. And, oh yeah, some people do prefer this with someone actually singing the vocal part, so here's a lovely version if you MUST.

Also, regarding the scrolling score, I thought to include regular bar numbers this time after forgetting to include them for The Blue Bird. But though I really like the look of infinite scrolling, the one problem I haven't really solved is that this means the key signature disappears. I've experimented with keeping a static one in the left margin, but that ends up looking awful. As these songs of Stanford and Chausson each have lots of flats, it's an awkward thing to miss. What's odd is that, when reading music in real time, I find it very disturbing not to be able to see a key signature (if obscured by a book holding the music open, for example), but somehow it doesn't bother me aesthetically here. Might be in part because I know the music so well, but I'm not really providing the notation for performers here anyway. It's more about the way notation abstractly represents the sounds....

NOTE: The translations used in this post are closely based on this English version by Peter Low.

Monday, January 18, 2021

Blue birds, wind chimes, minor sevenths, and mine craft

First of all, the music Marcel was proudly playing is one of the primary themes from the wildly popular world-building game Minecraft. (Working regularly with middle and high school boys has reinforced how much video game music is now an essential part of the musical vernacular.)

Apparently like most Minecraft music, the vibe is ambient and free-floating and not all that distinctively thematic, so it was odd to have it calling out to me. After a little more research and studying the MIDI information Marcel left behind, I realized that the music he'd been taught (likely by a friend) uses only five adjacent black keys. "Black key" music is notable for a few reasons. First of all, beginning piano students are often taught to play simple melodies on black keys first because the more obvious visual groupings make them easier to find.

So, I decided to make a YouTube version of my recording. I used the magical Lilypond to create a score suitable for slow scrolling across the screen. Curious about those minor sevenths, I also decided to add a Roman numeral harmonic analysis below. The analysis probably isn't perfect, and you're free to ignore it, but I indicated all minor seventh chords (occurring in various inversions and over various scale degrees) in blue to show how often Stanford leans that way. Although the minor seventh chord is not a standard part of a blues progression, the inherent sadness in this mildly dissonant harmony works really well for Stanford's sonic depiction of blueness.

Kind of...