Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Fugue in Royal David's City

I've mentioned again and again that I tend to be most interested in composing when I'm building on something familiar. I need to get over this, because I think it's less about an inability to create good melodies and more about lazily taking advantage of the cachet that an existing melody carries. I don't just mean that I don't think listeners will believe in my tunes; it's more that I don't believe in them myself until I've lived with them for a while. (As I've often remarked, the world of classical music trades on this kind of cachet all the time. The famous tune of Beethoven's 9th is about as undistinguished as can be, but we don't tend to hear it that way because it carries so many strong associations from within and without.)

Perhaps getting over this hangup would make a good New Year's Resolution, but for now, I continue to find inspiration in Erica Sipes' ongoing musical advent series (see yesterday's post), in which she plays piano settings of well-known Christmas tunes. I was thinking it would be fun to try my hand at such a setting, but I'm also old-fashioned, so I decided to make it a fugue. I find the fuguing process to be fascinating because, though there are some very standard signposts to hit, the form invites the subject to find its own path - which is another way of saying, I didn't expect this to come out at all like it did.

The subject is based on the very Anglican "Once in Royal David's City," which is the traditional opener in the legendary King's College Lessons & Carols service. Honestly, I used to think of this as a pretty dull melody, but I've heard and sung to Nathan Skinner's inspiring orchestration at the Park Street Church Lessons & Carols for many years, and it has grown on me, especially the way in which Nathan harmonizes the downbeat of the final verse as a I 6/4 chord instead of the standard I, creating a wonderful sense of forward momentum. (You can hear the interlude leading into the final verse starting around 7:00 of this video from last Sunday evening. Wife of MMmusing is sitting first chair cello, Daughter of MMmusing is playing in the first violin section, and I'm standing there singing in the congregation - but I won't say where. The interlude also features a series of imitative entries, which suggest a fugal texture.)

Though my little fugue (started and finished on the same day) begins fairly properly, I do indulge in some parallel fifths and unprepared modulations along the way because...well, fugues are really about freedom, not rules. I wish my piano was better tuned here (perhaps yesterday's Beethoven banging didn't help), but I'm still pleased with the outcome:

2017 UPDATE: New recording with [virtual] organ.

Perhaps getting over this hangup would make a good New Year's Resolution, but for now, I continue to find inspiration in Erica Sipes' ongoing musical advent series (see yesterday's post), in which she plays piano settings of well-known Christmas tunes. I was thinking it would be fun to try my hand at such a setting, but I'm also old-fashioned, so I decided to make it a fugue. I find the fuguing process to be fascinating because, though there are some very standard signposts to hit, the form invites the subject to find its own path - which is another way of saying, I didn't expect this to come out at all like it did.

The subject is based on the very Anglican "Once in Royal David's City," which is the traditional opener in the legendary King's College Lessons & Carols service. Honestly, I used to think of this as a pretty dull melody, but I've heard and sung to Nathan Skinner's inspiring orchestration at the Park Street Church Lessons & Carols for many years, and it has grown on me, especially the way in which Nathan harmonizes the downbeat of the final verse as a I 6/4 chord instead of the standard I, creating a wonderful sense of forward momentum. (You can hear the interlude leading into the final verse starting around 7:00 of this video from last Sunday evening. Wife of MMmusing is sitting first chair cello, Daughter of MMmusing is playing in the first violin section, and I'm standing there singing in the congregation - but I won't say where. The interlude also features a series of imitative entries, which suggest a fugal texture.)

Though my little fugue (started and finished on the same day) begins fairly properly, I do indulge in some parallel fifths and unprepared modulations along the way because...well, fugues are really about freedom, not rules. I wish my piano was better tuned here (perhaps yesterday's Beethoven banging didn't help), but I'm still pleased with the outcome:

2017 UPDATE: New recording with [virtual] organ.

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

A Carol for Beethoven

Carol of the Beethoven

I was asked by pianist/blogger friend Erica Sipes the other day if I had any favorite piano arrangements of The Carol of the Bells. Curiously, the first thing that popped into mind was this fun little Kabalevsky teaching piece:

Of course, it doesn't really qualify since it's basically in major instead of ominous minor - speaking of which, while considering the Ukranian carol tune, I realized for the first time that its basic four-note motif is also the beginning of the famous Die irae chant, which has been featured by so many composers. It occurred to me briefly that Liszt's fabulous Totentanz, based on the Dies irae, could easily be converted into some sort of wild exploration of those sweet, silver bells, but I chose only to go this far:

...and that was far enough.

However, the stupid tune was dancing in my head and soon it had danced its way into Beethoven's 5th. I'm proud to say I whipped this up in just a few hours, though I wish I'd invested more time in making it easier to play. But, since Beethoven's birthday comes but once a year, I figured I'd better get it posted today, so there it is [at the top of the post].

Happy Beethoven Day!

Friday, November 20, 2015

What if the great composers wrote the music for the closing credits of '80's TV shows? Part III

So far, there are only three classical music tunes that have "appeared to me" as perfect for the closing credits of '80s TV shows, so today's feature subject will wrap up this series...for now.

I honestly haven't done much serious reflecting about what particular musical qualities have sparked these connections. In the case of the Franck, the syncopations perhaps stand out as unusual for a big, serious symphony, which is why that tune always seemed a fish out of water in the concert hall. The Dvořák and today's Beethoven theme just strike me as giddier than usual (not a bad thing!) for their contexts: high energy, some unexpected accents, simple building blocks that make them catchy, etc. I'm sure some would say that adding a "Hooked on Classics" beat to any foursquare tune would make it work as well as the themes I've chosen, but I'm skeptical. It can be hard to shake such qualities as grandiosity, elegance,* and seriousness of purpose. For better or for worse, Dvořák, Franck, and Beethoven have found the secret sauce.

The scherzo of Beethoven's silliest sonata, Op. 31, No.3, has stood out to me as unusual since I first heard it in college (in the 80's!). The first and last movements of the sonata actually have more misdirections and sleights of hand, so they're more comical in terms of syntax and surprise, but the second movement scherzo, with it's bouncing L.H. accompaniment, has the most endearingly goofy tune. I'm pretty sure I always thought it had a "pop" sensibility, with it's combination of smooth melodic contours, bouncy articulations, and a kind of natural off-beat emphasis (not so much from the sf's after beat 2, but in the way the left hand pattern naturally gives a kick on beat 2). It even looks funny to me, I suppose because of all the staccato dots:

I remember hearing Richard Goode perform this sonata live about 25 years ago, and although I suppose people weren't literally laughing out loud, it was the flat-out funniest performance I can ever remember hearing/seeing - funny on purely good-natured musical grounds, not because of lyrics, staging, or whatever. (OK, Goode is a bit of a character, and his floppy hair was a character of its own back in 1989.)

I've been disappointed in looking for a performance on YouTube that captures that unpolished spirit, though I like this one by the always interesting Lazar Berman:

Berman's approach is still more "studied" than I'd like (I'll get to that in a second), but it strikes me that the humor of this movement has to do with how all those semi-serious diversions, pauses, and hints of turmoil always end up back at the same silly, banal place: the irresistably "easy listening" tune.

To be honest, my conception of this music was changed forever when I first heart Don Dorsey's synthesized "Beethoven or Bust" album, also back in the '80's. The whole album screams "'80's," and I recommend it as a highly entertaining artifact of its time. (The "Rage Over a Lost Penny" is a great starting point.) I wouldn't say this album has "ruined" the Scherzo for me, though; rather, it's revealed its true destiny in a way that makes every well-intentioned piano performance a little disappointing.

Whereas I did the synthesizing of Dvořák and Franck on my own, I didn't really feel like I could improve on what Dorsey had already done with this Beethoven scherzo (subtitled "Western" on the album), so I've simply made my own 30-second cut to close out an episode of "Charles in Charge." Just for the record, I've never watched a single episode of "Charles in Charge," but it seems like the embodiment of '80's TV at its most '80's, and the Beethoven/Dorsey Scherzo is a perfect way to cap an episode. (Also for the record, "Charles in Charge" may have one of the worst theme songs in TV history. I'll let you do the legwork finding it.)

So, that's the end of this series for now. I've even made a little YouTube "composerTV" playlist, with a couple of bonus additions from the MMmusing archives. Hopefully all of these tunes will find their way into pop culture one way or another.

* "Elegance," for me, is where Haydn's famously light-hearted themes fail the "80's" test - that is to say, the Haydn comic tunes are too elegant.

I honestly haven't done much serious reflecting about what particular musical qualities have sparked these connections. In the case of the Franck, the syncopations perhaps stand out as unusual for a big, serious symphony, which is why that tune always seemed a fish out of water in the concert hall. The Dvořák and today's Beethoven theme just strike me as giddier than usual (not a bad thing!) for their contexts: high energy, some unexpected accents, simple building blocks that make them catchy, etc. I'm sure some would say that adding a "Hooked on Classics" beat to any foursquare tune would make it work as well as the themes I've chosen, but I'm skeptical. It can be hard to shake such qualities as grandiosity, elegance,* and seriousness of purpose. For better or for worse, Dvořák, Franck, and Beethoven have found the secret sauce.

The scherzo of Beethoven's silliest sonata, Op. 31, No.3, has stood out to me as unusual since I first heard it in college (in the 80's!). The first and last movements of the sonata actually have more misdirections and sleights of hand, so they're more comical in terms of syntax and surprise, but the second movement scherzo, with it's bouncing L.H. accompaniment, has the most endearingly goofy tune. I'm pretty sure I always thought it had a "pop" sensibility, with it's combination of smooth melodic contours, bouncy articulations, and a kind of natural off-beat emphasis (not so much from the sf's after beat 2, but in the way the left hand pattern naturally gives a kick on beat 2). It even looks funny to me, I suppose because of all the staccato dots:

I remember hearing Richard Goode perform this sonata live about 25 years ago, and although I suppose people weren't literally laughing out loud, it was the flat-out funniest performance I can ever remember hearing/seeing - funny on purely good-natured musical grounds, not because of lyrics, staging, or whatever. (OK, Goode is a bit of a character, and his floppy hair was a character of its own back in 1989.)

I've been disappointed in looking for a performance on YouTube that captures that unpolished spirit, though I like this one by the always interesting Lazar Berman:

Berman's approach is still more "studied" than I'd like (I'll get to that in a second), but it strikes me that the humor of this movement has to do with how all those semi-serious diversions, pauses, and hints of turmoil always end up back at the same silly, banal place: the irresistably "easy listening" tune.

To be honest, my conception of this music was changed forever when I first heart Don Dorsey's synthesized "Beethoven or Bust" album, also back in the '80's. The whole album screams "'80's," and I recommend it as a highly entertaining artifact of its time. (The "Rage Over a Lost Penny" is a great starting point.) I wouldn't say this album has "ruined" the Scherzo for me, though; rather, it's revealed its true destiny in a way that makes every well-intentioned piano performance a little disappointing.

Whereas I did the synthesizing of Dvořák and Franck on my own, I didn't really feel like I could improve on what Dorsey had already done with this Beethoven scherzo (subtitled "Western" on the album), so I've simply made my own 30-second cut to close out an episode of "Charles in Charge." Just for the record, I've never watched a single episode of "Charles in Charge," but it seems like the embodiment of '80's TV at its most '80's, and the Beethoven/Dorsey Scherzo is a perfect way to cap an episode. (Also for the record, "Charles in Charge" may have one of the worst theme songs in TV history. I'll let you do the legwork finding it.)

So, that's the end of this series for now. I've even made a little YouTube "composerTV" playlist, with a couple of bonus additions from the MMmusing archives. Hopefully all of these tunes will find their way into pop culture one way or another.

* "Elegance," for me, is where Haydn's famously light-hearted themes fail the "80's" test - that is to say, the Haydn comic tunes are too elegant.

Thursday, November 19, 2015

What if the great composers wrote the music for the closing credits of '80's TV shows? Part II.

I'll bet you thought there wasn't really going to be a Part II. But, no, the truth is, I really do have these thoughts (see subject heading) and it's an important part of my therapy to meet them head on in this way. (Part I is here.)

So today we investigate a melody which I have to admit I really don't like, although I guess other people enjoy it. I was having a Facebook discussion with a friend recently and we were both agreeing that César Franck wrote more than a few over-ripe tunes,* many of which he stuffed into his Symphony in D Minor.

I even featured one of those tunes (from the first movement) in my recent post about Sigmund Spaeth's notorious "The Great Symphonies." Spaeth also has words for the finale's theme (which Spaeth transposes from D to A so more people can sing these snappy lyrics):

And here's what I wrote about this tune in my very Franck Facebook discussion:

See, I really do have those thoughts.

I had not remembered Spaeth's lyrics when I also chose to salute the symphony's syncopations in verse, but surely that jaunty rhythm is one of the reasons I could hear the music working perfectly in this context:

Frankly, Franck's pervasive chromaticism might've been a bit much for TV, although perhaps it could be symbolic of all the deception roiling beneath that broad Texas sky. I went ahead and left the notes as Franck left them, but I'm sure in the proper harmonic/orchestral dress, this theme would sound EXACTLY right for this show.

I admit it's not quite as big a success musically as my "Hooked on Classics" Dvořák from my last post, but that's partly because the symphonic texture here is so dense and really needs more pruning than I care to do. Incidentally, two themes from the scherzo of Dvořák's "New World" Symphony have always struck me as perfect cowboy tunes, and if this was a "What if the great composers wrote the music for the closing credits of '50's Westerns?" post, I'm sure you'd be seeing me take these tunes to their logical conclusions. (Note that the composer's original orchestration would've worked fine then...which is boring.) Forget Copland, Ives, and Gershwin. Maybe Dvořák really is America's greatest composer!

Yes, there will be a Part III! (and here it is)

* In fairness to César, I'll concede that this is one of the most perfect tunes ever - and it's a canon!

So today we investigate a melody which I have to admit I really don't like, although I guess other people enjoy it. I was having a Facebook discussion with a friend recently and we were both agreeing that César Franck wrote more than a few over-ripe tunes,* many of which he stuffed into his Symphony in D Minor.

I even featured one of those tunes (from the first movement) in my recent post about Sigmund Spaeth's notorious "The Great Symphonies." Spaeth also has words for the finale's theme (which Spaeth transposes from D to A so more people can sing these snappy lyrics):

And here's what I wrote about this tune in my very Franck Facebook discussion:

See, I really do have those thoughts.

I had not remembered Spaeth's lyrics when I also chose to salute the symphony's syncopations in verse, but surely that jaunty rhythm is one of the reasons I could hear the music working perfectly in this context:

Frankly, Franck's pervasive chromaticism might've been a bit much for TV, although perhaps it could be symbolic of all the deception roiling beneath that broad Texas sky. I went ahead and left the notes as Franck left them, but I'm sure in the proper harmonic/orchestral dress, this theme would sound EXACTLY right for this show.

I admit it's not quite as big a success musically as my "Hooked on Classics" Dvořák from my last post, but that's partly because the symphonic texture here is so dense and really needs more pruning than I care to do. Incidentally, two themes from the scherzo of Dvořák's "New World" Symphony have always struck me as perfect cowboy tunes, and if this was a "What if the great composers wrote the music for the closing credits of '50's Westerns?" post, I'm sure you'd be seeing me take these tunes to their logical conclusions. (Note that the composer's original orchestration would've worked fine then...which is boring.) Forget Copland, Ives, and Gershwin. Maybe Dvořák really is America's greatest composer!

Yes, there will be a Part III! (and here it is)

* In fairness to César, I'll concede that this is one of the most perfect tunes ever - and it's a canon!

Tuesday, November 17, 2015

What if the great composers wrote the music for the closing credits of '80's TV shows? Part I.

For some reason, I sometimes hear well-known classical themes and think, "Hmm, that sounds like a tune that would work great for the closing credits of an 80's or 90's TV show." But, of course, I don't usually do anything about it.

It is based on this...

...and that's really the way Wings ended each week, though the opening was more Schubertian in mood.

Now, there was a time (during the late '80s and early '90s!) when I would've been horrified at someone doing this to Schubert's transcendentally beautiful music.

But, that was some time ago...

So, I present Exhibit A of what might've been if the great composers...you know:

You can't tell me that doesn't work!

If you'd like to hear the entire Dvorak movement fitted with this hip '80's vibe, here you go:

The rhythm track isn't always synced up right, but it seems there should be a limit on how much time one spends doing this sort of thing.

If you'd like to hear the "other" version, here it is.

It came to mind today when I was talking to Daughter of MMmusing about her rehearsal of the first movement of this quartet. I was trying to remember how the fourth movement went, and when its main tune popped up in my memory, it immediately took me back....not to Bohemia or the 19th century America that supposedly inspired Dvořák, but rather to quick scene changes, fast scrolling credits, and...Tony Danza?

Now available: Part II & Part III

See also: The Reich of Spring in San Francisco

For the record, there is this bit of precedent, for which I can take no "credit":

It is based on this...

...and that's really the way Wings ended each week, though the opening was more Schubertian in mood.

Now, there was a time (during the late '80s and early '90s!) when I would've been horrified at someone doing this to Schubert's transcendentally beautiful music.

But, that was some time ago...

So, I present Exhibit A of what might've been if the great composers...you know:

You can't tell me that doesn't work!

If you'd like to hear the entire Dvorak movement fitted with this hip '80's vibe, here you go:

The rhythm track isn't always synced up right, but it seems there should be a limit on how much time one spends doing this sort of thing.

If you'd like to hear the "other" version, here it is.

It came to mind today when I was talking to Daughter of MMmusing about her rehearsal of the first movement of this quartet. I was trying to remember how the fourth movement went, and when its main tune popped up in my memory, it immediately took me back....not to Bohemia or the 19th century America that supposedly inspired Dvořák, but rather to quick scene changes, fast scrolling credits, and...Tony Danza?

Now available: Part II & Part III

See also: The Reich of Spring in San Francisco

Wednesday, November 4, 2015

The Fall of the Rake (or "The Rake's Lack of Progress")

This morning I looked out into my backyard and saw, as I captioned this photo on Facebook, "a bright golden haze on the mead'r."

My father inquired, in a friendly way, as to whether there was a plan to remove those beautiful leaves. A few comments down the way, I found myself channeling Auden and Stravinsky as a way of expressing how badly I fail at this kind of yard work. I wrote:

The concept is modeled on the heartrending final scene of Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress, in which poor Tom has lost his mind and his love (Anne Trulove, whom he now imagines to be Venus) and descended into madness. I've been lucky enough to have two wonderful tenors who could carry this scene a couple of times in Opera Scenes productions, and both times I've found the whole extended finale deeply moving. You can hear the whole scene starting here in this playlist, but I'm particularly fond of the late Jerry Hadley's interpretation.

And with that, I take my leave...

My father inquired, in a friendly way, as to whether there was a plan to remove those beautiful leaves. A few comments down the way, I found myself channeling Auden and Stravinsky as a way of expressing how badly I fail at this kind of yard work. I wrote:

Well, whenever I've tried to tame leaves, my rake's progress has generally followed the Tom Rakewell trajectory, and it ends with me delusional and babbling incoherently in Britten-like parlando style:

♫ I have baggèd each leaf, and so I leave work for a season to sleep in this bed.I'm strangely proud of that couplet. I picture our failing hero standing in the middle of a scene like the one above, believing his raking is done, and seeing the leftover leaves as a gift from his estranged beloved. (I can't imagine why she'd "leave" him.)

And, lo, here my Venus hath laid leafy pillows of gold where I now rest my head. ♫

The concept is modeled on the heartrending final scene of Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress, in which poor Tom has lost his mind and his love (Anne Trulove, whom he now imagines to be Venus) and descended into madness. I've been lucky enough to have two wonderful tenors who could carry this scene a couple of times in Opera Scenes productions, and both times I've found the whole extended finale deeply moving. You can hear the whole scene starting here in this playlist, but I'm particularly fond of the late Jerry Hadley's interpretation.

And with that, I take my leave...

Saturday, October 31, 2015

Boo Review Two

I'm a little disappointed that I haven't created many frightening videos (depending on your point-of-view) in the past two years since I last posted a Halloween sampler. It's especially remarkable given that I've dabbled in 12-tone composition (see here, here, here, and here) and viola shredding.

Indeed, yesterday's "trill of doom" journey* may be the best dabbling with darkness I've down lately, so I'm just gonna celebrate today with a reprise of 2013's reprise of 2011's Halloween post. Yeah, you could click those links, but I've done the work for you by copying everything below. Cue whirring time-travel arpeggios as we head back to October 31, 2013 and then back to 2011:

Boo Review (originally posted, 10/31/13)

Two years ago, I posted a set of creepy videos (many mine) for Halloween, and it's coming back from the dead here. So, my work for today is mostly done, but I'll just begin by adding this (from last month) to the mix.

...and now, let's revisit the past:

Boo (originally posted, 10/31/11)

I'm giving myself only five minutes to write this Halloween post, relying as it does on already existing multimedia:

For quietly scary fun, there's this mashup I created a couple of years ago, combining the final two movements of Chopin's Piano Sonata No.2. It features the most famous funeral march ever with the terrifying ghostly echoes of the whirlwind finale:

So, that's to set the mood.

Then there are these two videos which I regret to say I didn't create. But they're frightening visual companions to Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire. First...

The companion video is no longer on YouTube, but you can still view it on Facebook here.

So, no, I didn't make those, but they did inspire me to make this, which is pretty unsettling: (Check out the look on the sun's face.)

Now, let's pause for an ad from J. Peterman.

And if you like Stravinsky jabbing at you unexpectedly, you might give this a try. [Click on image below.]

Finally, in light of the surprising intersection of wintry snow cover and October we're having here in the Northeast [remember, this was 2011], you can find all manner of creepiness in these various versions of Schubert's "Der Leiermann," from his song-cycle Winterreise. (None of these are mine: this is just a little playlist I put together for Twitter-based reasons a couple of days ago.) I'll embed one here, but you can find the others by following the link just above:

Enjoy the day!

* And back here in 2015, I've realized that my "Just trillin' with doom" post title from yesterday was inspired by this "Alan Gilbert, chillin' with death" article I found a few days ago while looking for this fantastic video:

So that's something new for this year, even though it's not new and I had nothing to do with creating it.

Indeed, yesterday's "trill of doom" journey* may be the best dabbling with darkness I've down lately, so I'm just gonna celebrate today with a reprise of 2013's reprise of 2011's Halloween post. Yeah, you could click those links, but I've done the work for you by copying everything below. Cue whirring time-travel arpeggios as we head back to October 31, 2013 and then back to 2011:

Boo Review (originally posted, 10/31/13)

Two years ago, I posted a set of creepy videos (many mine) for Halloween, and it's coming back from the dead here. So, my work for today is mostly done, but I'll just begin by adding this (from last month) to the mix.

...and now, let's revisit the past:

Boo (originally posted, 10/31/11)

I'm giving myself only five minutes to write this Halloween post, relying as it does on already existing multimedia:

For quietly scary fun, there's this mashup I created a couple of years ago, combining the final two movements of Chopin's Piano Sonata No.2. It features the most famous funeral march ever with the terrifying ghostly echoes of the whirlwind finale:

So, that's to set the mood.

Then there are these two videos which I regret to say I didn't create. But they're frightening visual companions to Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire. First...

The companion video is no longer on YouTube, but you can still view it on Facebook here.

So, no, I didn't make those, but they did inspire me to make this, which is pretty unsettling: (Check out the look on the sun's face.)

Now, let's pause for an ad from J. Peterman.

[2015 UPDATE: If you've never heard this song, you might enjoy watching this version today:

]

Here's my own little take on Pierrot lunaire, combined with some Stravinsky. Creepy clown!

And if you like Stravinsky jabbing at you unexpectedly, you might give this a try. [Click on image below.]

Finally, in light of the surprising intersection of wintry snow cover and October we're having here in the Northeast [remember, this was 2011], you can find all manner of creepiness in these various versions of Schubert's "Der Leiermann," from his song-cycle Winterreise. (None of these are mine: this is just a little playlist I put together for Twitter-based reasons a couple of days ago.) I'll embed one here, but you can find the others by following the link just above:

Enjoy the day!

* And back here in 2015, I've realized that my "Just trillin' with doom" post title from yesterday was inspired by this "Alan Gilbert, chillin' with death" article I found a few days ago while looking for this fantastic video:

So that's something new for this year, even though it's not new and I had nothing to do with creating it.

Friday, October 30, 2015

Just trillin' with doom

Alex Ross has a new article in The New Yorker focusing on the mysterious "trill of doom" that interrupts the beautiful opening theme of Schubert's final piano sonata. Michael Agger, Ross's fellow New Yorker-er, promoted the article with the following tweet:

[If you'd like to hear all fifteen minutes of this movement, here's my unedited, live performance, which I don't think I'd listened to since 2006. It's got some rushing and other issues here and there, but I didn't mind listening to it just now. Also, I don't take the exposition repeat which András Schiff insists must be taken - that'll save you five minutes. I prefer my trill to Schiff's, anyway.]

So, finally, here's that trill (Leon Fleisher's version) finding its way into other contexts:

Happy Halloween!

“It’s the most extraordinary trill in the history of music.” @alexrossmusic on Schubert, now with TRILL AUDIO: http://nyr.kr/1WlNPwYTo which Ross responded:

Soon, all @NewYorker articles will be outfitted with TRILL AUDIOThis got me to thinking about what else this trill might disrupt, and...well, before we get to that, here's what the trill sounded like in a 2006 performance by yours truly:

[If you'd like to hear all fifteen minutes of this movement, here's my unedited, live performance, which I don't think I'd listened to since 2006. It's got some rushing and other issues here and there, but I didn't mind listening to it just now. Also, I don't take the exposition repeat which András Schiff insists must be taken - that'll save you five minutes. I prefer my trill to Schiff's, anyway.]

So, finally, here's that trill (Leon Fleisher's version) finding its way into other contexts:

Happy Halloween!

Friday, October 9, 2015

Turning the page...

I've said it before and I'll say it again: "I love a good mistake." I have strong memories as a young musician of being fascinated when a clarinetist clonked a passage somewhere in the middle of the Met's broadcast of the Ring Cycle. In the midst of all those hours of fantastic playing, there was something particularly gratifying and life-affirming about hearing such a moment of humanity. (My family taped all four of the operas, and that's the moment I most remember watching and re-watching.) I also remember well a low-budget family VHS of a Russian production of The Nutcracker in which one of the partygoing dancers got caught on the wrong side of the closing stage curtain. (In retrospect, I suppose this could have been an intentional bit of comedy.) I can still hear exactly what the orchestra was playing at that moment, and any time I hear that bit of music again, I instantly see that poor Russian woman fighting her way under the big velvet monster.

I've written many posts about this perverse attraction of mine. Here I discussed indelible memories of Suzuki students crushing a chord in Veracini; here I detailed a wide variety of memorable miscues, with a Mendelssohn misreading, a Dvorak missed shift, a Grieg misprint and a Ravel missed landing all taking a bow and making me smile. One of my worst-ever "can't stop laughing" struggles occurred years ago when I was turning pages for my piano teacher in a performance of the Franck Violin Sonata on a retirement home piano that needed retiring itself. During the performance of the manic second movement, I can still vividly remember the sight of old, broken ivories literally flying off the keyboard; I felt tears stream down my face as I tried to hold back laughter.

Not surprisingly, notable in-concert mistakes make the rounds among musicians every now and then because they're so strangely compelling. There's Maria Pires surprised to hear the orchestra starting the wrong concerto, Christian Zacharias stopping because a cellphone interrupts his Haydn (isn't Haydn supposed to love surprises?), and the resourceful violist who took up a cellphone ring tune for a quick bit of improvisation. But those aren't mistakes made by the performers in the moment.

Today, Jessica Duchen posted a video of a virtual Victor Borge routine breaking out at a violin recital due to a series of page-turning mishaps. In this performance by superstar violinist Christian Tetzlaff of the Brahms "F-A-E" Scherzo, Tetzlaff tries unsuccessfully to execute a quick page turn and comedy ensues.* There's so much to enjoy here that I couldn't resist making my own little annotated version.

Original, unannotated video is here.

What to Enjoy (I've now studied this thing like the Zapruder film):

- 0:18 Tetzlaff has less than two full measures (in a very quick tempo) to turn. He lifts the page with his bow hand, but the page flips back on him. It's on!

- 0:20 Probably my favorite thing is that his bow has returned to the violin, so he now tries to resume Brahms while fixing the music with his left hand, which is, um, also important in violin playing. The first two notes he's supposed to play are a G-A above middle C. He gamely plays them both on the open A string while trying to restore order.

- 0:21 He realizes the left hand isn't up to the task (it would have to reach far across his body to grab the page from the right) and that bowing isn't doing much good without the other hand, so he bails for a second and uses both hands to whip the page over...

- IMPORTANT POINT: The page turner is a very accomplished violinist who hears right away that something is amiss and looks up at Tetzlaff.

- 0:22 ...and the music goes crashing to the floor.

- 0:23 It's almost as if the force of the music falling pulls Tetzlaff towards it, and so, while having immediately resumed playing (with what must be a heightened sense of scherzo energy), he stomp-marches over to the piano to look over the piano score. Pianist Lars Vogt looks amused, though it's hard to tell for sure given the video quality.

- Meanwhile, our intrepid page-turner, Anna Reszniak, is up in a flash and moves through the space vacated by Tetzlaff to pick up the music and reset it. She checks the pages and turns to what she must think/hope is the right place.

- 0:30 Tetzlaff glances over at the violin stand and apparently doesn't see the right page, because he resumes playing from the piano score while Reszniak heads back to her position, looking back to see that something probably isn't quite right.

- 0:33 - 0:53 Music by Brahms.

- 0:53 The music has reached a low ebb before the final big buildup, and it's about time for Reszniak to turn the last page in the piano score.

- 0:56 She turns - and a loose page comes tumbling out. It's the final page, but at least Vogt has the left-side page still in front of him. He grins again. Suspense!

- 0:58 Reszniak starts back towards Tetzlaff.

- 0:59 Tetzlaff gracefully counters her, moving back with a little hop in his step to let Reszniak cross in front of him this time to retrieve the loose page.

- 1:02 She carefully places it back on the piano, as Tetzlaff crosses around her back towards the piano so he can see the music!

- 1:04 Reszniak calmly turns the violin part to the right place and circles back to her seat as Tetzlaff counters back to his place at the violin stand. All is well as...

- 1:10 ...the violin soars to the final big climax. The drama has been perfectly timed, and the unrehearsed footwork of Tetzlaff and Reszniak looks as effortless as the ice routines of Torvill and Dean.

I enjoy all of this in part because I've been in such situations before and know well how strangely thrilling it is to have a sudden extra layer of difficulty putting everyone on red alert (like that time when the lights went out). Seconds feel like minutes and every sense is heightened. Teztlaff, especially, had to make multiple split-second decisions, all while negotiating Brahms's high-wire act.

Actually, something kind of like this happened to me last Saturday night. I was accompanying a voice recital, reading the music from an iPad and using a pedal to turn pages. In a fairly straightforward song, I somehow turned a page ahead? Or perhaps panicked and turned back to fix what didn't need fixing? I actually don't remember exactly what happened, and I wasn't sure for a second (felt like a minute) if I needed to tap the screen to go back or forward. I sort of half-heartedly kept playing something semi-random with one hand while tapping the screen with the other, and can remember realizing that the soprano was half-glancing back at me. Then suddenly everything was fine again.

Of course, any live performance involves an exciting combination of 1) relying on deeply rooted muscle memory and 2) reacting at a split-second level to what's going on around. In rehearsed performances, there's always the danger of falling too much into routine and losing the exhilaration of being in the moment, and though I'm sure Tetzlaff regrets having to leave out a few measures (and playing an eighth-note G with an open A), I wouldn't be surprised if he and Vogt (and the audience!) found themselves experiencing an extra gear of musical excitement in what is already a hard-driving piece. (We can be sure Reszniak's heart was beating a little faster, though she may have enjoyed the music least of all.) They were living out the desperate emotions that Brahms had encoded so long ago.

As for me, I can't get enough of it, as you can see below. After all, there's humor in repetition.

Of course, any live performance involves an exciting combination of 1) relying on deeply rooted muscle memory and 2) reacting at a split-second level to what's going on around. In rehearsed performances, there's always the danger of falling too much into routine and losing the exhilaration of being in the moment, and though I'm sure Tetzlaff regrets having to leave out a few measures (and playing an eighth-note G with an open A), I wouldn't be surprised if he and Vogt (and the audience!) found themselves experiencing an extra gear of musical excitement in what is already a hard-driving piece. (We can be sure Reszniak's heart was beating a little faster, though she may have enjoyed the music least of all.) They were living out the desperate emotions that Brahms had encoded so long ago.

As for me, I can't get enough of it, as you can see below. After all, there's humor in repetition.

See also: My end is my beginning

* I also wrote once about a clearly audible page turn I cherish in a Beaux Arts Trio recording of the Ravel trio - but the only "mistake" there was how loudly the turn sounded. Yeah, I made a video then, too:

Saturday, October 3, 2015

Pugilistic Pianism

Sometimes, the less said, the better, so I'll keep this simple.

Someone posted this on Facebook yesterday:

And, perhaps inevitably, having thought about what "Rockymaninoff" might sound like, this ended up happening:

See also: The Rite of Spring Sonata

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

Founts of Inspiration

[If you don't want to read 1000+ words about music right now, you can just skip to the end and hear the music.]

I don't tend to refer to myself regularly as a "composer," though compositions sometimes seem to happen. (Poetry, too. See recent post re: accidental verse.) I suppose it's mostly that I don't compose regularly, and that so many of my compositions are based on pre-existing material. Of course, just about anything is based on pre-existing material to some degree, but I tend to find inspiration mostly when 1) I have a familiar musical idea as a starting point, and 2) I have a particular performance purpose in mind.

The idea of starting with something familiar connects, at a fairly deep level, with my own tendency to be more interested in music that I know than in music that's new to me. I fully understand that this can be limiting, and I try to fight it, though I think it's also fair to say that this kind of attitude partly defines what "classical music" is as a cultural phenomenon.

[At its most positive, returning again and again to the known is a way to experience the natural pleasure that recognition brings; recognition of a tune or style or whatever provides a perceptive framework which can make it easier to process other details and connections. Of course, there's a partial paradox in that music has to begin life as unknown and somehow cross over into the known, or whatever you want to call it. I guess the point is that, as a composer, I like to cheat by starting with something from "the inside."]

Anyway, I believe I'm fully capable of coming up with my own original musical ideas, but I just haven't spent much time doing that. However, working as a church musician gives me plenty of opportunities to compose with pre-existing materials as I'm a big fan of the chorale prelude model for service music.

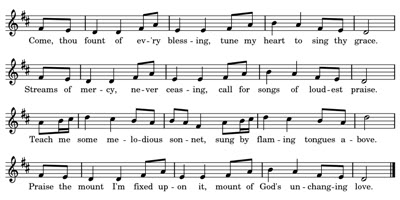

This past Sunday, the church was celebrating a summer service trip members of our congregation had taken working with the admirable Appalachia Service Project, so we'd chosen hymns that relate to that mission and that have a folksy, American flavor. Among the hymns was the ever-popular "Come, thou fount of every blessing," which I've found is the rare hymn that is pretty well-liked across the high-church/low-church spectrum.

As it happened, I already had planned to have my teenage daughter on hand to play a fiddle tune during Communion. (Technically, "Hector the Hero" is Scottish, but it's in our "music we can play with virtually no prep" rep. Daughter of MMmusing has a pretty busy life!) And if you don't happen to know "Come, thou fount of every blessing," here's what its tune (Nettleton) sounded like when Daughter of MMmusing played it eleven years ago at age five:

Rough, but sweet.

Speaking of which, since I was already going to have my "house violinist" in the house on Sunday, my mind turned to Charles Ives' Violin Sonata No. 2. Its last movement, subtitled "The Revival," happens to be a meditation on "Come, thou fount of every blessing" which whips itself up into a fervent climax, before ending simply.

[The hymn tune makes its first clear appearance around 1:15, though it's hinted at before.]

It's possible I'm writing this post just to boast that my daughter can be handed five pages of Ives (I gave her the piano score to make it easier for us to stay together) on a Saturday night and perform them beautifully and idiomatically about 14 hours later as the prelude. Ives' sonata isn't exactly Appalachian, but it certainly embodies the American spirit, and it has the composer's trademark combination of rough and sweet. This finale is immensely gratifying to play.

Ives is, of course, one of the best examples of a composer who loved working with pre-existing material. As it happens, I had also done some composing around "Nettleton" this summer when I needed something solemn but uplifting as recessional for a memorial service at which the hymn was sung. So, I reprised that piece on Sunday as the postlude, and am presenting it here today for anyone who might be interested.

I always like it when the postlude is either based on a tune from the day and/or when it is in the same key as the final hymn that precedes it, but I got a nice bonus surprise on Sunday just before I started postluding. Between the recessional hymn and the postlude, comes the spoken Dismissal:

It will have to fall to others to decide whether this composition is successful, but I'll say a bit about the compositional process, since that kind of thing interests me. The music opens in a way that is intentionally formulaic, beginning with a simple scalar descent in the bass that morphs into the hymn tune at the end of the second bar. As I recall, the "alleluia" motif just kind of happened as I was trying out different ways of countering the tune in the pedal. However, there are some interesting ways in which the complexity builds as tune and [newly christened] "alleluia" motif play off each other.

First of all, as the first phrase of the tune is finishing up in the pedal, the "alleluia" motif suddenly runs through the entire A section of the tune very quickly:

One thing that's interesting about this is that at the very moment the "right hand" is quoting the tune, it also seems to be breaking free of the formulaic melodic patterns that have persisted until this moment. It becomes independent by means of imitation.

The tune itself has a simple AABA structure. After the first two statements of 'A' have been heard in the pedal, a strange little interlude intervenes. First of all, the "alleluia" motif now anticipates the pitches of the 'B' part of the tune in m.10, while the "left hand" (not pedal) repeats the F#-E-D sequence which both opens and closes the 'A' section. (That's a really lovely feature of this tune that I don't remember having noticed before. Its end is its beginning.)

More importantly, you might noticed that the rests have disappeared from the treble staff above, and the "alleluia" rhythm is replaced by the "teach me some" rhythm that opens part 'B' of the tune. However, this motif, without the eighth note rest, occupies only three-quarters of a beat in this 3/2 meter, which means that, depending on how one hears and feels things, the right hand features four beats against the three of the left hand.

It's a fun little metrical interplay that isn't quite the same as the typical "4 against 3" because the right hand rhythms can easily be perceived in different ways. However they're perceived, the effect is that the 'B' section of the piece feels considerably less settled. Metrical order is restored just before the "recap" in which the final 'A' section is stated in m.24.

That's probably more than needs to be said about a piece that lasts less than two minutes, but as happens often once I've gotten some distance from the creative process, the various compositional procedures slip into the background as I listen to or play the music, and somehow it just sounds right. Because now I know it. (If only I could always write pieces I already knew, I might write much more!)

You can listen to the entire piece below. (The words, of course, are not intended to be sung.) If, for some reason, you're interested in playing it, please let me know! I'd love to hear a "real organist" play it.

I don't tend to refer to myself regularly as a "composer," though compositions sometimes seem to happen. (Poetry, too. See recent post re: accidental verse.) I suppose it's mostly that I don't compose regularly, and that so many of my compositions are based on pre-existing material. Of course, just about anything is based on pre-existing material to some degree, but I tend to find inspiration mostly when 1) I have a familiar musical idea as a starting point, and 2) I have a particular performance purpose in mind.

The idea of starting with something familiar connects, at a fairly deep level, with my own tendency to be more interested in music that I know than in music that's new to me. I fully understand that this can be limiting, and I try to fight it, though I think it's also fair to say that this kind of attitude partly defines what "classical music" is as a cultural phenomenon.

[At its most positive, returning again and again to the known is a way to experience the natural pleasure that recognition brings; recognition of a tune or style or whatever provides a perceptive framework which can make it easier to process other details and connections. Of course, there's a partial paradox in that music has to begin life as unknown and somehow cross over into the known, or whatever you want to call it. I guess the point is that, as a composer, I like to cheat by starting with something from "the inside."]

Anyway, I believe I'm fully capable of coming up with my own original musical ideas, but I just haven't spent much time doing that. However, working as a church musician gives me plenty of opportunities to compose with pre-existing materials as I'm a big fan of the chorale prelude model for service music.

This past Sunday, the church was celebrating a summer service trip members of our congregation had taken working with the admirable Appalachia Service Project, so we'd chosen hymns that relate to that mission and that have a folksy, American flavor. Among the hymns was the ever-popular "Come, thou fount of every blessing," which I've found is the rare hymn that is pretty well-liked across the high-church/low-church spectrum.

As it happened, I already had planned to have my teenage daughter on hand to play a fiddle tune during Communion. (Technically, "Hector the Hero" is Scottish, but it's in our "music we can play with virtually no prep" rep. Daughter of MMmusing has a pretty busy life!) And if you don't happen to know "Come, thou fount of every blessing," here's what its tune (Nettleton) sounded like when Daughter of MMmusing played it eleven years ago at age five:

Rough, but sweet.

Speaking of which, since I was already going to have my "house violinist" in the house on Sunday, my mind turned to Charles Ives' Violin Sonata No. 2. Its last movement, subtitled "The Revival," happens to be a meditation on "Come, thou fount of every blessing" which whips itself up into a fervent climax, before ending simply.

[The hymn tune makes its first clear appearance around 1:15, though it's hinted at before.]

It's possible I'm writing this post just to boast that my daughter can be handed five pages of Ives (I gave her the piano score to make it easier for us to stay together) on a Saturday night and perform them beautifully and idiomatically about 14 hours later as the prelude. Ives' sonata isn't exactly Appalachian, but it certainly embodies the American spirit, and it has the composer's trademark combination of rough and sweet. This finale is immensely gratifying to play.

Ives is, of course, one of the best examples of a composer who loved working with pre-existing material. As it happens, I had also done some composing around "Nettleton" this summer when I needed something solemn but uplifting as recessional for a memorial service at which the hymn was sung. So, I reprised that piece on Sunday as the postlude, and am presenting it here today for anyone who might be interested.

I always like it when the postlude is either based on a tune from the day and/or when it is in the same key as the final hymn that precedes it, but I got a nice bonus surprise on Sunday just before I started postluding. Between the recessional hymn and the postlude, comes the spoken Dismissal:

LEADER: Let us go forth in the name of the Lord. Alleluia, alleluia....and in that moment of hearing those "alleluias," I realized that the primary motif of my postlude has the same rhythmic profile as a spoken "alleluia," so the music felt righter than I'd expected.

PEOPLE: Thanks be to God. Alleluia, alleluia.

It will have to fall to others to decide whether this composition is successful, but I'll say a bit about the compositional process, since that kind of thing interests me. The music opens in a way that is intentionally formulaic, beginning with a simple scalar descent in the bass that morphs into the hymn tune at the end of the second bar. As I recall, the "alleluia" motif just kind of happened as I was trying out different ways of countering the tune in the pedal. However, there are some interesting ways in which the complexity builds as tune and [newly christened] "alleluia" motif play off each other.

First of all, as the first phrase of the tune is finishing up in the pedal, the "alleluia" motif suddenly runs through the entire A section of the tune very quickly:

One thing that's interesting about this is that at the very moment the "right hand" is quoting the tune, it also seems to be breaking free of the formulaic melodic patterns that have persisted until this moment. It becomes independent by means of imitation.

The tune itself has a simple AABA structure. After the first two statements of 'A' have been heard in the pedal, a strange little interlude intervenes. First of all, the "alleluia" motif now anticipates the pitches of the 'B' part of the tune in m.10, while the "left hand" (not pedal) repeats the F#-E-D sequence which both opens and closes the 'A' section. (That's a really lovely feature of this tune that I don't remember having noticed before. Its end is its beginning.)

More importantly, you might noticed that the rests have disappeared from the treble staff above, and the "alleluia" rhythm is replaced by the "teach me some" rhythm that opens part 'B' of the tune. However, this motif, without the eighth note rest, occupies only three-quarters of a beat in this 3/2 meter, which means that, depending on how one hears and feels things, the right hand features four beats against the three of the left hand.

It's a fun little metrical interplay that isn't quite the same as the typical "4 against 3" because the right hand rhythms can easily be perceived in different ways. However they're perceived, the effect is that the 'B' section of the piece feels considerably less settled. Metrical order is restored just before the "recap" in which the final 'A' section is stated in m.24.

That's probably more than needs to be said about a piece that lasts less than two minutes, but as happens often once I've gotten some distance from the creative process, the various compositional procedures slip into the background as I listen to or play the music, and somehow it just sounds right. Because now I know it. (If only I could always write pieces I already knew, I might write much more!)

You can listen to the entire piece below. (The words, of course, are not intended to be sung.) If, for some reason, you're interested in playing it, please let me know! I'd love to hear a "real organist" play it.

Friday, September 25, 2015

Adding Words to Wordless Music

With my 12 Composers of Christmas turning ten this December, I've been working on a new SATB choral version of this little music history sampler. A couple of years ago, I added a video with a recording featuring my homemade "junior chorale" singing the tune, but I figured having a full choir afforded the opportunity to get the singers involved in the musical quotations that are all over the piano part. Hopefully, I'll be able to debut a recording of this arrangement in time for the holidays and those end-of-semester review sessions.

For now, I'll just focus on one little bit of problem-solving. The composer for Day 6 is Franz Schubert, represented by the sextuplets that permeate his legendary Erlkönig. (Yes, technically they're marked as triplets, but they basically function as sextuplets.)

Both hands gets their own iconic versions of the sextuplets. For pianists, it's those insanely repeating right hand octaves that make this song memorable and truly terrifying, and though the Swingle Singers found a way to sing them, my arrangement leaves the octaves to the piano. However, the most distinctive hook in the whole song is the left hand motif that begins with a rising sextuplet scale. (Curiously, for this most melodically gifted of composers, the vocal part is mostly declamatory - except when the bad guy sings [1:25] his sickly sweet seductions - and the closest thing to a vocal hook is the child's cry [3:08] of "Mein Vater, mein Vater," which includes only two different pitches.)

So, I decided I'd let the choral basses in on the action by having them sing along with the left hand, which left me with the question of what syllables they should sing. The Swingles, not surprisingly, do a jazzy duhbaduh-duhbaduh-dum-dum-dum for the fast notes, but I found myself defaulting to doodlely-doodley-doo-doo-doo. Somehow the "oo's" make it seem more ominous, while the "doodlely" has a kind of playfulness I also like.

Anyway, it was only after I'd mostly finished the arrangement that I thought consciously about the unquestionable source for my "lyric." I had a distinct memory of Buddy Sorrell singing it as a comically ominous warning in some episode of The Dick Van Dyke Show - in fact, I'm sure I would've seen/heard Buddy's version several times before I ever heard how Schubert used this motif, though I've never spent much time thinking about the connection.

It took a little Googling (so many ways to spell "doodlely"), but I finally found my way to Episode 38: "Like a Sister." Sally's fallen for a flashy singer (played by Vic Damone), and Buddy anticipates a bad outcome, communicated through music instead of words. In the high-quality moving cellphone video below, you can also hear how the soundtrack cues pick up on Buddy's vocal as a little leitmotif.

Vocalizing instrumentally conceived musical ideas has its own history though, and I don't just mean when a character like George Costanza mimics some music he's excited about. (By the way, Jason Alexander nails this bit, in which he's asked to sing something about as singable [0:38] as Schubert's repeating octaves.)

(Oh, and perhaps it's not so surprising that Seinfeld includes this smart bit of classical vocalizing, since the GREATEST CLASSICAL MUSIC EPISODE IN TV HISTORY is Curb Your Enthusiasm's "Trick or Treat," in which Seinfeld mastermind Larry David first whistles Wagner and then wildly wields Wagner as an act of revenge. More on that here.)

But, of course, many music lovers have been tempted to go the extra, sometimes fateful step, and add actual words to instrumental tunes. This topic could go in many directions. In fact, I just tracked down this commercial that I used to see over and over back in the days when I was watching reruns of Dick Van Dyke after school. It references "Stranger in Paradise," "Our Love," "Full Moon and Empty Arms," and "Tonight we love," popular songs based on tunes by Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Tchaikovsky again. (I don't know how Chopin's "I'm Always Chasing Rainbows" didn't make it into this commercial.)

However, I think it's the music educators who've done the most harm in this realm - the folks who use the "just add words" technique on the classics to help us learn to remember these abstract tunes, never worrying about what parasitic harm those syllables can do over time. So, how do I even discuss such a sensitive topic without doing more harm?

Well, I'll just mention a little book I used to check out of my local library: The Great Symphonies, by Sigmund Spaeth. The curious Dr. Spaeth (who apparently made something of a career for himself in what Leonard Bernstein used to refer to as the "music appreciation racket*") decided that the best way to help listeners navigate sophisticated symphonic structures was to nail the tunes to some of the worst lyrics imaginable.

On the no-longer-active Dial M for Musicology blog, I once made a cautionary comment about Spaeth's book to which Phil Ford replied: "Sigmund Spaeth! That book is a musical neuroweapon — you get Speath’s idiot mnemonics in your head and it will forever overwrite your prior hearings of the music."

So, do I dare unleash any of these neuroweapons now? And I'll just add that a distinguished Twitter follower seemed genuinely alarmed when I tweeted a few of these out last week She wrote:

OK, you've been warned.

To ease us in, I'm gonna start with what might be my least favorite tune in the symphonic repertoire (though this might be because I read Spaeth's words so many years ago), this rousing bit of bombast from Franck's Symphony in D Minor, which you can hear at about 14:55 here.

The words are awful, but it's Franck's chromaticisms that really make me queasy.

You probably won't get this next example stuck in your head because it's so awkward to sing [1:00]:

And, finally, just one more example which is SO STUPID that I really don't think it will get stuck in your head either. I don't think it would be possible to write worse lyrics to the truly inspired opening of Mozart's 40th ("full of laughter and fun" ?):

I can confidently say that I've laughed at these words many times over the years and they've never upset my feelings for Mozart.

Obviously, I have a bit of a love/hate relationship with this book. I even ordered my own copy on Amazon a few years back when I couldn't find my old copy (which I think I'd bought at a book sale at the same library where I first found the book). Anyone who's read this blog knows that I don't hold musical masterworks so sacred that they should never be re-imagined, and I also think that approaching music with a playful spirit is almost always a good thing.

BUT THE BEST NEWS IS: Spaeth's book is now available for perusing in full online. So, if you enjoy this sort of thing, then by all means, follow that link and see what you think.

There are, of course, some other "just add words" paths I haven't explored here, most notably the kinds of [often inappropriate] words that music students have passed around the halls of conservatories. I'll never be able to hear Chopin's 3rd Ballade without blushing a little, but I won't say why. Sometimes, it's best to stick with dummy lyrics like "doodle-ly, doodle-ly, doo, doo, doo...."

* In fairness, as evidenced by the fact that I used to check out Spaeth's book frequently, I've enjoyed the musical appreciation racket myself at various times.

P.S. For the record, although I know and respect some people who like it, I find the "Beethoven's Wig" series even worse than Spaeth because it include those inane arrangements/performances which I won't even link to - but I'm happy to say that none have gotten stuck in my head.

For now, I'll just focus on one little bit of problem-solving. The composer for Day 6 is Franz Schubert, represented by the sextuplets that permeate his legendary Erlkönig. (Yes, technically they're marked as triplets, but they basically function as sextuplets.)

Both hands gets their own iconic versions of the sextuplets. For pianists, it's those insanely repeating right hand octaves that make this song memorable and truly terrifying, and though the Swingle Singers found a way to sing them, my arrangement leaves the octaves to the piano. However, the most distinctive hook in the whole song is the left hand motif that begins with a rising sextuplet scale. (Curiously, for this most melodically gifted of composers, the vocal part is mostly declamatory - except when the bad guy sings [1:25] his sickly sweet seductions - and the closest thing to a vocal hook is the child's cry [3:08] of "Mein Vater, mein Vater," which includes only two different pitches.)

So, I decided I'd let the choral basses in on the action by having them sing along with the left hand, which left me with the question of what syllables they should sing. The Swingles, not surprisingly, do a jazzy duhbaduh-duhbaduh-dum-dum-dum for the fast notes, but I found myself defaulting to doodlely-doodley-doo-doo-doo. Somehow the "oo's" make it seem more ominous, while the "doodlely" has a kind of playfulness I also like.

Anyway, it was only after I'd mostly finished the arrangement that I thought consciously about the unquestionable source for my "lyric." I had a distinct memory of Buddy Sorrell singing it as a comically ominous warning in some episode of The Dick Van Dyke Show - in fact, I'm sure I would've seen/heard Buddy's version several times before I ever heard how Schubert used this motif, though I've never spent much time thinking about the connection.

It took a little Googling (so many ways to spell "doodlely"), but I finally found my way to Episode 38: "Like a Sister." Sally's fallen for a flashy singer (played by Vic Damone), and Buddy anticipates a bad outcome, communicated through music instead of words. In the high-quality moving cellphone video below, you can also hear how the soundtrack cues pick up on Buddy's vocal as a little leitmotif.

Vocalizing instrumentally conceived musical ideas has its own history though, and I don't just mean when a character like George Costanza mimics some music he's excited about. (By the way, Jason Alexander nails this bit, in which he's asked to sing something about as singable [0:38] as Schubert's repeating octaves.)

(Oh, and perhaps it's not so surprising that Seinfeld includes this smart bit of classical vocalizing, since the GREATEST CLASSICAL MUSIC EPISODE IN TV HISTORY is Curb Your Enthusiasm's "Trick or Treat," in which Seinfeld mastermind Larry David first whistles Wagner and then wildly wields Wagner as an act of revenge. More on that here.)

But, of course, many music lovers have been tempted to go the extra, sometimes fateful step, and add actual words to instrumental tunes. This topic could go in many directions. In fact, I just tracked down this commercial that I used to see over and over back in the days when I was watching reruns of Dick Van Dyke after school. It references "Stranger in Paradise," "Our Love," "Full Moon and Empty Arms," and "Tonight we love," popular songs based on tunes by Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Tchaikovsky again. (I don't know how Chopin's "I'm Always Chasing Rainbows" didn't make it into this commercial.)

[ Available on 8-track! ]

Well, I'll just mention a little book I used to check out of my local library: The Great Symphonies, by Sigmund Spaeth. The curious Dr. Spaeth (who apparently made something of a career for himself in what Leonard Bernstein used to refer to as the "music appreciation racket*") decided that the best way to help listeners navigate sophisticated symphonic structures was to nail the tunes to some of the worst lyrics imaginable.

On the no-longer-active Dial M for Musicology blog, I once made a cautionary comment about Spaeth's book to which Phil Ford replied: "Sigmund Spaeth! That book is a musical neuroweapon — you get Speath’s idiot mnemonics in your head and it will forever overwrite your prior hearings of the music."

So, do I dare unleash any of these neuroweapons now? And I'll just add that a distinguished Twitter follower seemed genuinely alarmed when I tweeted a few of these out last week She wrote:

Please stop posting those "Great Symphonies" excerpts. Burn that book. Those words can get into your head & ruin the music forever.How about I put a big picture of the book's cover here, and you only scroll down if you don't mind exposing yourself to what lies beneath?

OK, you've been warned.

To ease us in, I'm gonna start with what might be my least favorite tune in the symphonic repertoire (though this might be because I read Spaeth's words so many years ago), this rousing bit of bombast from Franck's Symphony in D Minor, which you can hear at about 14:55 here.

You probably won't get this next example stuck in your head because it's so awkward to sing [1:00]:

And, finally, just one more example which is SO STUPID that I really don't think it will get stuck in your head either. I don't think it would be possible to write worse lyrics to the truly inspired opening of Mozart's 40th ("full of laughter and fun" ?):

Obviously, I have a bit of a love/hate relationship with this book. I even ordered my own copy on Amazon a few years back when I couldn't find my old copy (which I think I'd bought at a book sale at the same library where I first found the book). Anyone who's read this blog knows that I don't hold musical masterworks so sacred that they should never be re-imagined, and I also think that approaching music with a playful spirit is almost always a good thing.

BUT THE BEST NEWS IS: Spaeth's book is now available for perusing in full online. So, if you enjoy this sort of thing, then by all means, follow that link and see what you think.

There are, of course, some other "just add words" paths I haven't explored here, most notably the kinds of [often inappropriate] words that music students have passed around the halls of conservatories. I'll never be able to hear Chopin's 3rd Ballade without blushing a little, but I won't say why. Sometimes, it's best to stick with dummy lyrics like "doodle-ly, doodle-ly, doo, doo, doo...."

* In fairness, as evidenced by the fact that I used to check out Spaeth's book frequently, I've enjoyed the musical appreciation racket myself at various times.

P.S. For the record, although I know and respect some people who like it, I find the "Beethoven's Wig" series even worse than Spaeth because it include those inane arrangements/performances which I won't even link to - but I'm happy to say that none have gotten stuck in my head.

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

Happy Freedom to Birthday

So I guess "Happy Birthday" is finally free.

Let's celebrate the new birthday of Happy Birthday.

I only wish I'd created the rest of these:

I don't know who created the last two, but if someone does, let me know. Oh, and somebody needs to combine those two into one.

UPDATE: Oh, and someone on Twitter just alerted me to the existence of this:

Sunday, September 20, 2015

For better or for verse...

I rarely set out to write verse, but sometimes it happens anyway.

Here's Manny in action:

As it happened today, I was sitting listening to our newly ordained curate deliver the sermon on a day she was celebrating the Eucharist for the first time. In a beautiful sermon about the symbolic meaning of opening one's arms, she talked about a class in seminary which was focused on the study of "manual acts." I don't think I'd ever heard this expression, but I can tell you that on hearing it, I kept thinking she was saying "the study of Emanuel Ax."

I thought later that Ax's playing is worth studying, and as the day progressed, these couplets emerged:

Piano expressions come not just from facts

that a treatise exacts via keyboard didacts.

One can learn lessons from manual acts

of Emanuel Ax that a manual lacks.

The fun part, of course, is that the final couplet sounds like it's repeating itself, especially when read by a synthesizer.

Here's Manny in action:

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

MM's Musical Manipulatives

It's been a quiet summer here on the blog, but I've been multimedia-ing away in the background and finally have something to show for it. I've been working on my (previously meager) programming chops for the past 6-7 months, which means that JavaScript (a programming language used for controlling web pages) is less of a mystery to me than it once was.

About four years ago, I put together a series of "integrated listening guides" for my own teaching - they allow the user to click through the landmarks of an analytical outline to jump instantly back and forth within an embedded score and video (or audio). The JavaScript I used was mostly copied and pasted from other sites I'd found online. I often understood very little about how the code worked, but kept applying virtual duct tape until I got the results I wanted, and indeed, I found these guides very useful in the classroom. They made it so easy to navigate a large musical structure on the fly as there's no time wasted turning pages or cueing up a video to the right point.

But there were plenty of drawbacks, especially in terms of cross-platform compatibility. Reliance on some flash elements meant the guides wouldn't work on iPads and the like, and reliance on the quirky Scribd platform for embedding the scores caused some limitations and made things look kind of clunky.* And, basically, it seemed like every six months or so, some web standard had changed so that the guides didn't work properly until I applied more virtual duct tape.

Anyway, over the past few weeks, I finally got around to updating these guides, and they now work much more elegantly, with a variety of improved features, including:

- Pages now turn automatically with the music!

- The outline automatically updates to highlight the section being played at the moment.

- Two of the guides (Brahms and Mozart) feature running captions that describe the music.

- Pages resize nicely according to the size of the browser window.

- The guides work pretty smoothly across a range of browsers and on iPads! (I assume they work fine in Android devices as well as long as the screen is big enough. They more or less work on my smallish Kindle Fire HD, though it's not a great user experience.)

- In the two Beethoven symphony guides, one can instantly jump back and forth within the first and second times though the repeated Exposition sections.

- The Beethoven "Eroica" guide includes the option of switching orchestras on the fly! The two performances (Järvi and Bernstein) feature very different tempi, but they nevertheless stay closely synced.

- Just for fun, you can speed up or slow down the performances.

In short, they do most of the things I'd want them to do, and I'm also gratified to say that I now understand 98% of how the JavaScript is working. In fact, much of the code is written from scratch. The guides available now include:

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 "Eroica," 1st mvt.

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 5, all four movements

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata, Op. 111, 2nd mvt.

- Brahms: Symphony No. 4, 4th mvt.

- Mozart: The Marriage of Figaro, Act II Finale

- Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto, 1st mvt.

I began referring to these guides a few years ago as "musical manipulatives" by analogy to the kinds of hands-on physical objects used to help teach math concepts. The idea here is that, for the student, grasping the structural relationships within a large-scale work can be daunting. These guides provide a framework for visualizing the structure as a whole and examining the components instantly. This makes it easy, for example, to compare various appearances of a theme in different keys and contexts. I've found this to be a great way to help explain the tonal features of sonata form. In the variation movements (Brahms and Beethoven Op.111), one can easily sample individual variations to see how they relate to each other. (Designing the guide for Op.111 helped me make sense of how the last few variations begin departing from the thematic structure.)

I've written before about the concept of storyboarding a piece by listening only to a few seconds of each segment to get a quick overview of the shape of things. In the new Beethoven "Eroica" guide, if you click on the "Big Bangs" link, you'll hear a relatively seamless performance that condenses 15.5 minutes to exactly 60 seconds of sforzando milestones.

A few years ago, commenter dfan wrote here:

A few years ago, commenter dfan wrote here:

I remember as a little kid when I suddenly realized that I actually could hold the whole structure of the first movement of Beethoven's 5th in my head and follow it from beginning to end, and that it actually made logical semantic sense in the same way that a long sentence does, rather than just being a continuous stream of arbitrary music that happened to end at some point. It was a real epiphany.That is the kind of perspective I hope these guides can help to provide. (Listening to the "Eroica" at double-speed, though kind of silly, is also an interesting way to get a bird's-eye perspective, a concept I explored here: listening at 10x!)

I realize I'm not the first to design something like this, though I think my design has some nice advantages over what I've seen before. The San Francisco Symphony's excellent "Keeping Score" series has an "Eroica" guide. (Warning: music starts playing right away. Bad design.) It certainly has more detail at some levels and a cleaner (though ugly) looking score, with a vertical bar that awkwardly lurches ahead every measure to show exactly where the music is. It also, most frustratingly, only includes excerpts, and never provides a structural view of an entire movement.

Touchpress's amazing Beethoven 9 app includes four perfectly synced performances, plus cool bells and whistles like a manuscript view, a little light-up orchestra simulation, tons of background information, and a constantly scrolling score (which I find a bit disconcerting). It's not easy to view the entire score at once, although a cool "curated score" option shows only the most "important" instruments at a given time to save space. Again, I feel what it does least well is keep a focus on the large-scale structure, as there's no option of viewing an outline while the music plays. It also has the notable disadvantage of only working on iOS devices. I've thought before about getting into mobile app development, but it's more gratifying in some ways to design a single site that works equally well on desktops, laptops, and tablets.