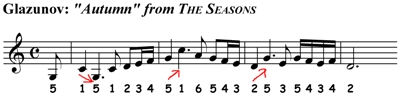

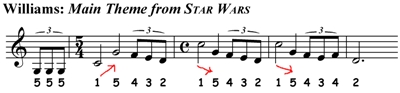

First, let's consider a possible source for Williams' most famous theme, the Main Title from Star Wars. The first time I heard the Bacchanal from the Autumn portion of Glazunov's ballet, The Seasons, I was playing in the cello section of an orchestra. I hadn't even noticed the connection until the conductor happened to mention it to a Pops audience.

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

[UPDATE: On 4/29, I added the arrows to the examples above and also renotated the Star Wars theme with the 5/4 bar which, I believe, is how Williams notates it. UPDATE 2: But I was wrong! The theme should be in 4/4 all the way. Oh well!]

The correct notation for that theme is:

The big difference is that where Glazunov goes down from 1-5, Williams goes up (1-5) and then vice versa, but each hammers away at do (1) and sol (5) at the expense of mi (3), giving the tunes their rugged, open qualities. In addition, both phrases end with similar gestures that stop on re (2), and the settings feature full orchestra with lots of percussion and lively backrhythms. Still, I consider this much less of a theft than Strauss/Superman (an amusing juxtaposition, what with Strauss's Nietzschean leanings and all), especially since I prefer the Williams theme to Glazunov. I can't say I've ever been drawn to much of anything by Glazunov. I've accompanied the violin concerto multiple times and the saxophone concerto a few times, but I'm always underwhelmed.

[That I prefer Williams to Glazunov in this case reminds me of a phrase Peter Burkholder uses when he notes that Handel borrowed from another composer, but "repaid with interest." (NAWM, p. 723.) When I first went looking online for that quote, I happened to discover that Burkholder is an editor for an entire website devoted to musical borrowing. I was a little disappointed to find that it's a giant bibliography, not an index of tunes; not quite a site for instant gratification, but certainly a place to get started looking at this issue more in-depth. I love the Internet. Now, back to my shallow offerings.]

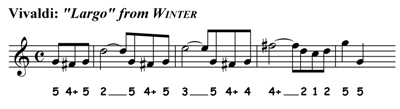

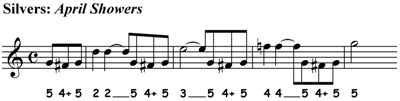

I'm sure others will have noticed this next connection, although I haven't found reference to it online. I can't imagine how anyone could miss the way that April Showers recalls this transition passage from the slow movement of Vivaldi's Winter Concerto:

Not only do we get our second straight instance of a work about the seasons, but the Four Seasons melody goes with these lines from the Winter sonnet: "To rest contentedly beside the hearth, while those outside are drenched by pouring rain." I strongly doubt that Louis Silvers and Buddy DeSylva had Winter in mind when they wrote April Showers for Al Jolson, especially since Vivaldi wasn't really rediscovered till well after 1921. That makes this 'reference' all the more remarkable. Then again, maybe they knew what they were doing, so they transferred the showers from early March to April to throw us off. Having just experienced a week of brutal April showers, I can attest that they can be wintry experiences.

Next we have a Schubert song (no, not from Winterreise) which, as it happens, I first heard in a Liszt arrangement for solo piano. I can't help but think that hearing Lob der Tränen played on piano is one of the factors that caused me immediately to hear the following as a forerunner of the famous piano melody from Chariots of Fire.

I think the similarities are pretty easy to detect here, even though the meters are different. Given my general fascination with the processes of translation and transcription, I especially like that I first heard Schubert's tune transfigured from voice to piano and that provided a gateway to hearing it transported to the 20th century. (As an aside, I don't think Vangelis's synthesized soundtrack has aged very well, although I do count myself a big fan of that movie.)

Now this last example requires a bit more explanation. My dear mother would not call herself a musician, but she's always held over me two proofs of superior musical affinity. 1.) She can whistle, and I cannot. 2.) She once heard a piano sonata on the radio and casually suggested it was Mozart; I, in the midst of undergraduate studies that included piano rep classes and the like, assured her that it was Haydn. Turns out I was suffering from Mozart/Haydn confusion, and she's never let me forget it.

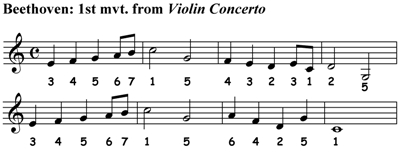

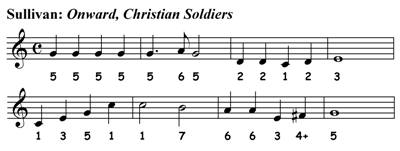

So, when she once suggested that this tune from Beethoven's Violin Concerto sounded like Arthur Sullivan's Onward, Christian Soldiers, I was flummoxed, but I knew I couldn't just dismiss her intuition. After all, she could whistle both tunes.

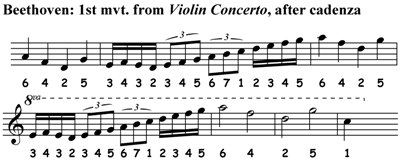

Never mind that this is one of Beethoven's most glorious works and this is the worst tune by Sir Arthur that I can think of. There must be a deeper connection that Mom was picking up on, and the truth is that I always sort of agreed with her. Well, the best that I can offer is that, in addition to how unrelentingly square the rhythmic and phrasing patterns are, they each feature an ascent up to do from m.5 to m.6, which is followed by a little wraparound phrase that starts on la (6). True, Sullivan's forces are marching forward to a half-cadence (note the F#) at m.8 whereas Beethoven gets right to a perfect authentic cadence. Crazy and tenuous as it is, I hear a distant connection in the way Beethoven later twice denies the perfect cadence when the violin whispers the tune post-cadenza, the fiddle landing on mi (3) a couple of times:

Never mind that this is one of Beethoven's most glorious works and this is the worst tune by Sir Arthur that I can think of. There must be a deeper connection that Mom was picking up on, and the truth is that I always sort of agreed with her. Well, the best that I can offer is that, in addition to how unrelentingly square the rhythmic and phrasing patterns are, they each feature an ascent up to do from m.5 to m.6, which is followed by a little wraparound phrase that starts on la (6). True, Sullivan's forces are marching forward to a half-cadence (note the F#) at m.8 whereas Beethoven gets right to a perfect authentic cadence. Crazy and tenuous as it is, I hear a distant connection in the way Beethoven later twice denies the perfect cadence when the violin whispers the tune post-cadenza, the fiddle landing on mi (3) a couple of times:

This is borderline insane, but I really do think I experience a kinship between the 6-5-3 structure here and the 6-3-5 at the end of the Sullivan excerpt above. (I'm ignoring the instances of 2, 4, and 4+ as passing notes.) Maybe I'm just trying to please my mother. The larger point here is that making connections, some more logical than others, is just what we do when we listen to music. We hear a succession of sounds and our brain goes into some sort of audio databank and says, "here's a match." Sometimes it's a match because we're hearing a work we already know, but sometimes it's a match because we make our own connections.

I'll close with this great little story about Erich Korngold from Oscar Levant's A Smattering of Ignorance.

- ...After this he asked for "The Man I Love" and, in sequence, Vincent Youmans' "Tea for Two." Then he turned triumphantly and said, "See - a note for note steal." This was incomprehensible to me and still is today, as I recall it, for even the slightest resemblance does not exist between the two songs - in mood, melodic line or harmony. (p. 72)

WORKS CITED: I don't feel too guilty about posting little audio snippets since I own these recordings, all the examples are quite short, and hopefully they might lead to someone actually seeking out the full recordings. However, I should at least cite my sources: Strauss, Superman, Glazunov, Star Wars, Vivaldi, April Showers, Schubert, Chariots, Beethoven, Soldiers.

1 comment:

I found your comments most illustrative!

I landed in your blog because for years I have been telling my musical friends (I cannot read music but as you say I can whistle) that the Star Wars theme sounded a lot like Glazunov and surely that was not a coincidence.

A recent repeat of this conversation led me to a google search... et voilà!

Keep the good work. It is a source of fun and most illuminating.

Post a Comment