Monday, April 30, 2007

Tune Theft Archive

Yet More Tune Theft

Our first victim is from the slow movement of Mozart's B-flat Violin Sonata, K. 378, which Melissa and I have played together. The sumptuously scored second subject is a dead ringer for the CRUSADER'S HYMN tune, which is most often associated with Fairest Lord Jesus.

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

It's not a particularly original melodic structure, but the tunes are so similar that the hymn jumped to mind the very first time I heard it on a Heifetz disc years ago. Note that even where the violin melody becomes more ornate, it still traces the same descent from do (1) down to re (2). [That Heifetz recording always amused me because, in the first movement, he plays the clearly accompanimental violin line at the beginning as if it were the main tune, while poor Brooks Smith is off in some distant sonic space. Listen to the difference in balance when the piano has the tune and then when Jascha takes it.]

Melissa also mentions that she hears the big tune from Rhapsody in Blue during this tender little sequence from the 2nd mvt. of the Franck Violin Sonata:

It's not exact [but see Update below] because the Franck is really in the minor and starts on the 1st scale degree whereas the Gershwin begins on the 3rd. (As with previous posts, I've notated all examples in C Major to make the comparisons easier.) Thus, Franck begins whole-step/half-step and the Gershwin vice versa, but each three-note stepwise ascent is followed by the characteristic octave drop. After that they go they're separate ways and inhabit very different worlds. Still, I think it's a pretty cool pairing, especially because the contexts are otherwise so different - kind of like some of the "How Dry I Am" variations in Bernstein's talk.

I also just remembered that from the very first time I heard the exquisite Countess/Susanna duet from the Marriage of Figaro, it sounded to me like the old folk-song "O Dear, What Can the Matter Be?":

Clearly they're not exactly the same, but those shapely second measures have an obvious kinship. Most notably, each outlines a triad by starting in the middle, going down and then up so that the high note is in the most unstressed rhythmic position; each then continues with a triad going down. This is one of those connections I wish I didn't hear - it took me a while to learn to sit back and enjoy the Mozart for what it is. In fact, I'm embarrassed to say it may have taken Stephen King, Andy Dufresne, and The Shawshank Redemption to open my ears. Isn't that the miracle of Mozart, though? He can create the most sublime moments out of seemingly mundane materials.

UPDATE (the next morning): I just realized I cheated Melissa's Franck/Gershwin parallel. If you listen to the climactic phrase of the big blue Rhapsody tune, you get something much closer to Franck. Not only do they each begin now "in the minor," but they each have a wandering, modulating quality since they occur in transitional spots. Apologies for not having picked up on this sooner. (I've renotated the Franck in A Minor to match the Gerswhin.)

Recording Sources: Mozart Violin, Fairest Lord Jesus, Franck, Gershwin, Mozart Duet, O dear

Saturday, April 28, 2007

Cowardly old world

In fact, the one thing I don't really like about Hugh Sung's Tablet PC approach is that you only get one page at a time (unless you're willing to read very small print). My dream scenario would have two full-sized pages across. Actually, I would still probably choose to "turn" once per page in such a way that the current page slides to the left and the new one appears on the right, meaning the most immediate notes would always be in view. Thus, there would be some flexibility about the timing of the switch. This is the approach I use when working with a bunch of single, unbound sheets. (The kind of thing students tend to bring into coachings.) Given that the Tablet PC's are quite expensive to begin with, I may have to wait a while before the double-sided screen size is affordable.

I like the idea, though, of not having to kick my left foot out for page-turns, especially since I'm such a soft-pedal addict. (Truthfully, I'd be better off getting that addiction under control.) I think rather than some special "turn" motion, the best option would be what we'll call the Dorothy approach - click the heels together and it's off to the Kansas of the next page. That way both piano pedals could still be engaged. It's a motion that could be accomplished quickly and easily, but hopefully not inadvertently. Of course, there also needs to be a 'go back' motion (toes together?) just in case. In fact, I'm amazed that Hugh Sung is willing to put up with all the things that could go wrong - battery dying, heavy computer falling off the rack, pedal switch sliding away, pages turning too fast - but he seems to be an intrepid sort, like all the great pioneers. He probably also knows his music well.

Thinking of the whole motion-activating problem reminds me of a dilemma I faced during our recent Opera Scenes programs. In this case, I was trying to motion-activate the page turns by signaling my old-fashioned human assistant with nods of the head. I'm pretty finicky about when the pages turn because - well, because I don't practice enough and I like to see every note. I've also noticed that, being such a sight-reader by nature, I get distracted when I can't see everything, no matter how well I know the music. This particular turner was very good about following my nods and, since some of the music goes by very fast, she relied on me more than following the score.

Unfortunately, it also turned out that, during the fastest and most hard-to-follow passages, I was sometimes cueing singers with head nods. So, yes, we had more than a few instances of pages turning when I was just trying to bring a singer in. This was very stressful, but it would have helped if I could have been less concerned about seeing every note. Because my entire page-to-eyes-to-brain-to-fingers-to-keys way of processing is so ingrained, I'm often surprised at how off-kilter I feel when, say, a book that's holding the music open is covering up the key signature. Now, I might know with no doubt that there are three sharps, but if they're out of view then everything feels wrong. It makes me realize that I'm doing constant little scans of the key signature as part of that whole eyes/brain/fingers subconscious processing. What a thing, the brain.

All this is to say that, although a new music concert seemed like a perfect opportunity to show off new technology, I'd probably be better off not debuting this experience with music I don't know well at all.

Friday, April 27, 2007

Brave new world

I'm already seriously thinking of trying this out when I perform a student composer's piano piece in a recital tomorrow night. However, there's one spot in the piece that really could use a page-turning pedal of some sort. (Having a human page-turner up there would just ruin it, of course.) I actually have a little programmable USB mouse that would work - if I'm wearing only socks. This mouse works well because the entire body acts as a programmable button (PageDown, in this case) when pushed down from either the left or right side. (No fussing with tiny click buttons.) I'm just not sure I could feel it with shoes on, but I haven't actually tried yet.

I also have the composer's score in Finale, so I've played around a bit with reformatting the page-turning problem a way, but I haven't found a solution. Also, I'm not really playing the piece all that well right now, so perhaps I should go practice it!

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

That was my idea!

Hugh Sung, the coordinator of accompanying at Curtis among other high-profile qualifications, is an early adopter of playing from a computer screen (a TabletPC) instead of sheet music AND he's developing ways of integrating live concert/recital visuals that are controlled by performers in real time. Those were my ideas! As you may recall, this happened to Kramer as well; that's why Kramerica Industries was born:

- (Kramer is reading the newspaper at the table)

KRAMER: Look at this, they are redoing the Cloud Club.

JERRY: Oh, that restaurant on top of the Chrysler building? Yeah, that’s a good idea.

KRAMER: Of course it’s a good idea, it’s my idea. I conceived this whole project two years ago.

JERRY: Which part? The renovating the restaurant you don’t own part or spending the two hundred million you don’t have part?

KRAMER: You see I come up with these things, I know they’re gold, but nothing happens. You know why?

JERRY: No resources, no skill, no talent, no ability, no brains.

KRAMER: (interrupts) No, no…time! It’s all this meaningless time. Laundry, grocery, shopping, coming in here talking to you. Do you have any idea how much time I waste in this apartment?

JERRY: I can ball park it.

Anyway, I've always been a big believer in reading things off of a screen. I'm one of what is still a very small minority of people who prefer reading at a computer to those old-fangled books, and I've always assumed it was only a matter of time before musicians discovered ways to use virtual sheet music. Ironically, just the other day I accompanied my daughter's violin playing in an impromptu performance at Grandma's house, and, since I had the music on my laptop but no printer, I just played off the screen. (I had to get my wife to be my page-tapper.) Turns out Hugh Sung's been doing this for awhile with a Tablet PC, and he's got his own page-changing pedal. I'd heard tell of others doing it as well, but he's really thought this through.

He's also been pioneering the use of visuals in performances. I've always felt that the Disney Fantasia model was underutilized in the music biz, and yet I'd never want to be involved in live performances in which the performers have to coordinate with an existing video. So, my dream has been to devise animations that could be conducted in time with the music. I dream, Mr. Sung does. It's not exactly what I have in mind, but I'm inspired by how creatively he's embracing the use of technology in performance. And now, before I buy my own Tablet PC and start bringing my imagined animations to life, I'd better prepare for class tomorrow. No wonder Monroica Industries hasn't taken off yet. Maybe I need an intern . . .

Monday, April 23, 2007

Gambling with entertainment

The thing is, I generally have pretty mixed feelings about going to Fenway. Not only is it annoying trying to find parking (though we had great success last night - a free spot about a 13-minute walk away) and getting in and out of the park (getting from our excellent field-level seats back out to the street at the end took at least 15-20 minutes) and paying $11.25 for substandard dinner for one (horrible chicken strips with soggy fries and a coke), but there's all the other variables any games involves. Will the weather be comfortable or not? (Last night: absolutely perfect. Last game I went to last year: unbearably hot.) Will the team play well or not? (That worked out well last night.) Will there be rude and distracting fans around? (Well, yes, always, but last night we had the compensatory pleasure of seeing two escorted from the premises.) Will the game last a tidy 2 1/2 hours or go on for more than 3 1/2? (Actually, with Sox-Yankees you almost know it will be the latter because both teams are so patient at the plate. I just went to ESPN.com to doublecheck and confirmed that Bobby Abreu saw 29 pitches last night in five at-bats. [UPDATE: He only swung at 8 of them!] He walked twice and struck out three times. That's not so interesting to watch, except when the pressure is at the greatest.)

To be honest, I am stunned that people continue to pay what they do for this sort of entertainment since it's such a gamble. We're very grateful for the family connections that made it possible for us to have great seats last night, but I can't imagine choosing on my own to spend what so many do on a regular basis. (The unruly guys must have spent a minimum of $30 each just on watery ballpark beer last night, not to mention that they were sitting in $105 seats - and they got sent home early.) I'm not saying it's a wasted experience to see your team lose, but sometimes it can be incredibly frustrating on many levels. Having grown up watching baseball and other sports mostly on TV, I'm pretty conditioned to climate-controlled comfort and instant replays, not to mention the freedom to just walk away from a bad game without feeling like a huge investment's been wasted.

Anyway, the other side of this is that when you're at a game like last night where everything comes together (weather, big win, tense drama, incredibly rare historic happening and Dice-K on the mound), it seems to make up for everything else. And the fact that things might not turn out right is so important. We stood there watching the incredibly hot Alex Rodriguez as the go-head-run at the plate in the 9th. With one swing he could've ruined everything - and that knowledge is what made the last out so thrilling. It's a great experience precisely because all 36,000 of us knew it might be a disaster - what could be worse than losing after hitting four straight home runs?

Imagine going to a symphony concert and knowing so little about how the concert will turn out - or even what's on the program. Maybe you'll hear Heifetz sear his way through the Tchaikovsky concerto, but maybe some average violinist will play the Glazunov concerto poorly. Maybe you'll hear a pulse-pounding performance of Israel in Egypt, but maybe you'll have to sit through Haydn's Creation. (Sorry, little personal bias there.) Maybe the concert will be almost over at 90 minutes, but a deceptive cadence will send the program spinning on into extra innings - of Schoenberg!

True, one never knows exactly how a live performance will turn out, but if you go to the BSO, you've got a pretty good idea. Go see the Red Sox and you may see ghastly errors, errant pitches, overaggressive swinging, etc. Or, you might see four home runs in a row. (But maybe hit by the bad guys.) I'm not a gambler, but the appeal here isn't that different - the thrill of the unkown. As devoted as I am to music, I haven't had a lot of shared audience experiences to compare with the sheer bedlam that ensued when Jason Varitek hit the fourth shot over the wall. Of course, that's only happened four other times in history! (Did I already mention that?)

By the way, this historic event can't compare with the time last summer when, in a game with much more on the line, the Dodgers hit four straight home runs with two outs in the ninth innning to tie a game they'd eventually win with a 10th-inning homer. Oh, and J.D. Drew happened to hit the second home run in the sequence last year and this year, playing for different teams of course. This is why I love sports. I'm going to try to think what the musical experience equivalent of that would be. (I'm going to fail.)

One last thing: before the game started, the big story was Dice-K mania since this was his first ever start against the Evil Empire. In the end, he was pretty mediocre and only a side-story, but when he threw his first few pitches, there were literally hundreds of flashes going off all over the park. It was a stunning sight - and almost seizure-inducing.

UPDATE: I can't believe I forgot to mention my favorite little thing about the game. Once the Yankees' starter had given up the four home runs, they were forced to turn for middle relief help to someone named Colter Bean. Maybe he'll become a great and famous pitcher (though he looks like a reject from some softball league), but it's hard to see the Yanks going all the way relying on Colter Bean. It was strangely comforting.

Saturday, April 21, 2007

Found Music

Basically, I accidentally started two different recordings at about the same time on my computer. I had recently sent a link to a colleague of a Mozart trio performance with my 7-yr-old daughter on violin, my wife on cello, and me on piano. Since I hadn't listened to it for awhile, I clicked on the e-mail link to sample it. Meanwhile, what I should've been doing was grading papers; I had in front of me a student-created listening guide for a Handel sonata for recorder, cello, and harpsichord and had gone to our school's online streaming music site to cue up that recording. Somehow, in the time it was taking my computer to get the Mozart started, I absent-mindedly started up the Handel and, lo and behold, the two performances started at almost exactly the same time.

All I can say is that I really enjoyed what followed, particularly because it creates such a constant bending of perception. The basic effect is of a warped sound-world where everything sounds out-of-tune. Occasionally, one or the other of the performances will come to the fore, but mostly I hear them as a single, loopy texture that I'd rather not try to analyze too much. It's just fascinating how two such elegant and transparent worlds can combine to create something in which they both seem to lose their identity.

What fun Ives would've had with this technology at hand. Actually, Mozart himself experimented with this idea in the Act I finale of Don Giovanni where the three dance bands are heard all at once. (True story: I was just trying to listen to that scene, but was confounded by my daughter practicing Vivaldi in the next room. I can't enjoy Mozart's ordered chaos in the midst of all this chaos!) I've also always enjoyed the goofy finale of All You Need is Love in which a Bach invention on trumpets mixes it up with In the Mood, Greensleeves, and She Love You, Yeah, Yeah, Yeah and I don't remember what else. The entrance of Greensleeves is especially vague and trippy.

Anyway, back to my little "duet for two trios." The funny thing is that, as spontaneous as its 'creation' was, I then felt tormented that I wouldn't be able to recreate it exactly as it was because I couldn't actually remember which had started first. Obviously, it doesn't really matter, but I've done my best to turn its wonderful impermanence into something that is fixed for all time and can be studied and deconstructed . . . or just enjoyed for for what it is. I have no idea, by the way, what it is. Here 'tis.

A Little Bell Busk Redux

I'd say that both the Joyce Hatto and the Joshua Bell stories have basically the same moral: context makes a huge difference. Hatto's recordings (all made by other pianists) received extra acclaim because of the powerful centripetal* force of her "biography"; Bell's playing was mostly ignored because the unwashed masses were unaware of his glittering biography - and because he didn't know how to busk.

This depressingly cynical little item from Soho the Dog+ suggests that much audience reception is based on a sort of confidence game in which listeners are manipulated into believing they're having an authentic experience. I don't really agree with this extreme sociological point-of-view, but HattoBell shows that there's some truth there. Certainly, the authentic performance practice movement has gotten a lot of mileage out of this trick.

- * Yes, I originally used the word centrifugal, until realizing I meant the opposite; thus, the edit.

- + Also, in reading the final paragraph above, I realize it looks as if Soho the Dog (Matthew Guerrieri) is the one being cynical. It's actually an article to which he refers which cynically examines the marketing of Chicago Blues to tourists. It's easy for any of us to be cynical about marketing, and rightly so, but I didn't mean to suggest that Guerrieri's entire outlook towards audiences is so negative.

Thursday, April 19, 2007

More Great Moments in Tune Theft History

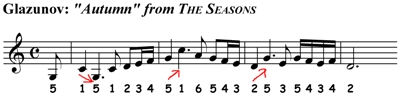

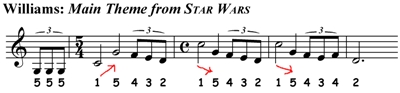

First, let's consider a possible source for Williams' most famous theme, the Main Title from Star Wars. The first time I heard the Bacchanal from the Autumn portion of Glazunov's ballet, The Seasons, I was playing in the cello section of an orchestra. I hadn't even noticed the connection until the conductor happened to mention it to a Pops audience.

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

[UPDATE: On 4/29, I added the arrows to the examples above and also renotated the Star Wars theme with the 5/4 bar which, I believe, is how Williams notates it. UPDATE 2: But I was wrong! The theme should be in 4/4 all the way. Oh well!]

The correct notation for that theme is:

The big difference is that where Glazunov goes down from 1-5, Williams goes up (1-5) and then vice versa, but each hammers away at do (1) and sol (5) at the expense of mi (3), giving the tunes their rugged, open qualities. In addition, both phrases end with similar gestures that stop on re (2), and the settings feature full orchestra with lots of percussion and lively backrhythms. Still, I consider this much less of a theft than Strauss/Superman (an amusing juxtaposition, what with Strauss's Nietzschean leanings and all), especially since I prefer the Williams theme to Glazunov. I can't say I've ever been drawn to much of anything by Glazunov. I've accompanied the violin concerto multiple times and the saxophone concerto a few times, but I'm always underwhelmed.

[That I prefer Williams to Glazunov in this case reminds me of a phrase Peter Burkholder uses when he notes that Handel borrowed from another composer, but "repaid with interest." (NAWM, p. 723.) When I first went looking online for that quote, I happened to discover that Burkholder is an editor for an entire website devoted to musical borrowing. I was a little disappointed to find that it's a giant bibliography, not an index of tunes; not quite a site for instant gratification, but certainly a place to get started looking at this issue more in-depth. I love the Internet. Now, back to my shallow offerings.]

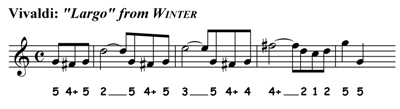

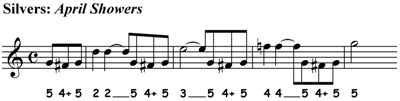

I'm sure others will have noticed this next connection, although I haven't found reference to it online. I can't imagine how anyone could miss the way that April Showers recalls this transition passage from the slow movement of Vivaldi's Winter Concerto:

Not only do we get our second straight instance of a work about the seasons, but the Four Seasons melody goes with these lines from the Winter sonnet: "To rest contentedly beside the hearth, while those outside are drenched by pouring rain." I strongly doubt that Louis Silvers and Buddy DeSylva had Winter in mind when they wrote April Showers for Al Jolson, especially since Vivaldi wasn't really rediscovered till well after 1921. That makes this 'reference' all the more remarkable. Then again, maybe they knew what they were doing, so they transferred the showers from early March to April to throw us off. Having just experienced a week of brutal April showers, I can attest that they can be wintry experiences.

Next we have a Schubert song (no, not from Winterreise) which, as it happens, I first heard in a Liszt arrangement for solo piano. I can't help but think that hearing Lob der Tränen played on piano is one of the factors that caused me immediately to hear the following as a forerunner of the famous piano melody from Chariots of Fire.

I think the similarities are pretty easy to detect here, even though the meters are different. Given my general fascination with the processes of translation and transcription, I especially like that I first heard Schubert's tune transfigured from voice to piano and that provided a gateway to hearing it transported to the 20th century. (As an aside, I don't think Vangelis's synthesized soundtrack has aged very well, although I do count myself a big fan of that movie.)

Now this last example requires a bit more explanation. My dear mother would not call herself a musician, but she's always held over me two proofs of superior musical affinity. 1.) She can whistle, and I cannot. 2.) She once heard a piano sonata on the radio and casually suggested it was Mozart; I, in the midst of undergraduate studies that included piano rep classes and the like, assured her that it was Haydn. Turns out I was suffering from Mozart/Haydn confusion, and she's never let me forget it.

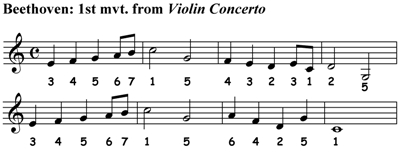

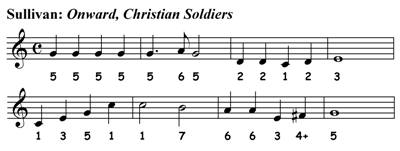

So, when she once suggested that this tune from Beethoven's Violin Concerto sounded like Arthur Sullivan's Onward, Christian Soldiers, I was flummoxed, but I knew I couldn't just dismiss her intuition. After all, she could whistle both tunes.

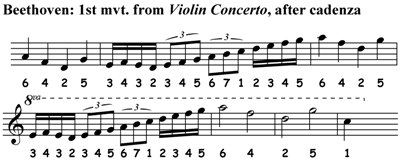

Never mind that this is one of Beethoven's most glorious works and this is the worst tune by Sir Arthur that I can think of. There must be a deeper connection that Mom was picking up on, and the truth is that I always sort of agreed with her. Well, the best that I can offer is that, in addition to how unrelentingly square the rhythmic and phrasing patterns are, they each feature an ascent up to do from m.5 to m.6, which is followed by a little wraparound phrase that starts on la (6). True, Sullivan's forces are marching forward to a half-cadence (note the F#) at m.8 whereas Beethoven gets right to a perfect authentic cadence. Crazy and tenuous as it is, I hear a distant connection in the way Beethoven later twice denies the perfect cadence when the violin whispers the tune post-cadenza, the fiddle landing on mi (3) a couple of times:

Never mind that this is one of Beethoven's most glorious works and this is the worst tune by Sir Arthur that I can think of. There must be a deeper connection that Mom was picking up on, and the truth is that I always sort of agreed with her. Well, the best that I can offer is that, in addition to how unrelentingly square the rhythmic and phrasing patterns are, they each feature an ascent up to do from m.5 to m.6, which is followed by a little wraparound phrase that starts on la (6). True, Sullivan's forces are marching forward to a half-cadence (note the F#) at m.8 whereas Beethoven gets right to a perfect authentic cadence. Crazy and tenuous as it is, I hear a distant connection in the way Beethoven later twice denies the perfect cadence when the violin whispers the tune post-cadenza, the fiddle landing on mi (3) a couple of times:

This is borderline insane, but I really do think I experience a kinship between the 6-5-3 structure here and the 6-3-5 at the end of the Sullivan excerpt above. (I'm ignoring the instances of 2, 4, and 4+ as passing notes.) Maybe I'm just trying to please my mother. The larger point here is that making connections, some more logical than others, is just what we do when we listen to music. We hear a succession of sounds and our brain goes into some sort of audio databank and says, "here's a match." Sometimes it's a match because we're hearing a work we already know, but sometimes it's a match because we make our own connections.

I'll close with this great little story about Erich Korngold from Oscar Levant's A Smattering of Ignorance.

- ...After this he asked for "The Man I Love" and, in sequence, Vincent Youmans' "Tea for Two." Then he turned triumphantly and said, "See - a note for note steal." This was incomprehensible to me and still is today, as I recall it, for even the slightest resemblance does not exist between the two songs - in mood, melodic line or harmony. (p. 72)

WORKS CITED: I don't feel too guilty about posting little audio snippets since I own these recordings, all the examples are quite short, and hopefully they might lead to someone actually seeking out the full recordings. However, I should at least cite my sources: Strauss, Superman, Glazunov, Star Wars, Vivaldi, April Showers, Schubert, Chariots, Beethoven, Soldiers.

Can You Read My Mind and Name That Tune?

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

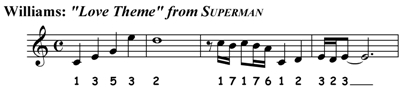

How melody functions is mysterious in many ways, but if a picture is worth a thousand words, then so are these examples. (Of course, that won't stop me from multiplying a few words here.) Note that the Superman theme doesn't start with Strauss's upbeat, but a sol-do upbeat-downbeat combo is so common that I don't really hear it as an essential part of the melodic fingerprint. Even more more interesting is that on beats 1, 2, and 3, Strauss uses do-re-mi (1-2-3) while Williams uses do-mi-so (1-3-5). That would seem to be a big difference, but our ears hear them as similar because they each ascend at an even pace and they're each so stable tonally. A tonic chord (harmonic homeplate) is composed of scale degrees 1, 3, and 5 which is how Williams begins, but 1 and 3 are really enough to define the tonic chord since the 5th is such a strong overtone of the tonic. Because 2 falls in an unstressed place in Strauss, it does nothing to disturb the tonic stability of 1 to 3. (I realize this is both more and less than various readers will want to know.)

[Click on the examples to hear them played.]

How melody functions is mysterious in many ways, but if a picture is worth a thousand words, then so are these examples. (Of course, that won't stop me from multiplying a few words here.) Note that the Superman theme doesn't start with Strauss's upbeat, but a sol-do upbeat-downbeat combo is so common that I don't really hear it as an essential part of the melodic fingerprint. Even more more interesting is that on beats 1, 2, and 3, Strauss uses do-re-mi (1-2-3) while Williams uses do-mi-so (1-3-5). That would seem to be a big difference, but our ears hear them as similar because they each ascend at an even pace and they're each so stable tonally. A tonic chord (harmonic homeplate) is composed of scale degrees 1, 3, and 5 which is how Williams begins, but 1 and 3 are really enough to define the tonic chord since the 5th is such a strong overtone of the tonic. Because 2 falls in an unstressed place in Strauss, it does nothing to disturb the tonic stability of 1 to 3. (I realize this is both more and less than various readers will want to know.)

The truth is that until I looked online for the Superman theme, I had remembered it as beginning 1-2-3, no doubt because these two tunes had become conflated in my mind. Why? (Can you read my mind?) Of course, it's that distinctive leap up to mi (3) an octave higher that leads to a sustained re (2) on the downbeat of the next bar. Notice that although the size of these intervals is different (Strauss leaps an octave, Superman a sixth), the effect is similar because they leap to the same scale degree and then land on re (2) which is one of the most unstable scale degrees because it points so strongly down to do (1). After that leap, the tunes seem to be completely different, but note that each ends by outlining a 1-3 ascent. Furthermore, there's an interesting mirroring as Strauss makes another leap up from m.3 into m.4 while Superman has an important leap down in m.3.

It's also notable that each tune begins in a similarly foursquare rhythmic pattern, but the crucial connection is certainly that registral leap up to mi-re (3-2). I can't help but wonder if, at some point in the compositional process, Williams was consciously aware that he was transfiguring Strauss's transfiguration theme; thus, the change from 1-2-3 to 1-3-5 might've been an intentional alteration that set his tune apart while not really sacrificing what makes it so appealing. That's pure speculation on my part, and I don't mean to imply anything sinister. He certainly took the idea in a different direction with the second phrase, although I find that part of the melody much less satisfying. I also never thought it made such a good song; that second phrase works much better as an orchestral motif than as bearer of these trite lyrics: "Can you read my mind? Do you know what it is you do to me?" Perhaps it's not surprising that Williams hasn't had very many successful pop songs.

TOMORROW: More Fun With Tune Theft

NOTE: Though I am a faithful reader of Soho the Dog, this post was already in the works before he quoted Strauss's theme in this one-of-a-kind cartoon; just a blogosphere coincidence which gives me a good excuse to send you there. Even harder to believe is that I'd been working on a concept for my own little cartoon series featuring two fin de siècle composers (not Strauss and Mahler) before I saw Soho's work. I think I'll put that idea to bed for awhile, while sympathizing with poor John Williams and his recycling of others' ideas. I'd also better get my other four favorite tune thefts up quickly before someone steals them! At least I appear to have been the first to memorialize Hatto and Bell in sonnets.Monday, April 16, 2007

Wind and weather

Friday, April 13, 2007

Rex the Stickman

Maybe I'll live to regret this, but another busy week has slowed my posting habit. (I'm typing this at intermission of a recital I'm accompanying, my second today.) I really enjoyed reading this blogger's analysis of one of his early literary works, so I couldn't resist linking to a little book I wrote for my kid sisters when I was . . . younger. My ever creative Mom had made little fabric books (about 1-inch tall) with real pages and we had fun turning them into books. The family classic Rex the Stickman, my first real opus, was one of the results.

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

Bell Failure

The Bad Bard of the Blogosphere is back. I was there for you when Joyce Hatto needed ode-ing, and now this story is popping up all over, although at a fraction of Hatto levels. (It's a mere fraction of that story as well, so that's why this only gets two sonnets instead of six.)

a fiddling Bell who's quite well known

went busking in D.C. and toted

his Strad to play the Bach Chaconne.

He played his heart out for an hour.

He played with virtuoso power.

The passers-by went passing by

with hardly an attentive eye.

But why? When Mr. Bell is slated

to play the finest concert halls,

no seats are left; they line the walls

to hear him, even when inflated

demand means it costs much, much more

than sitting on a station floor.

So what's the moral of the story?

Are average folks so unaware

of beauty? Maybe, but before we

assume the worst, it's only fair

to mention that a subway station

is really not the best location

for Bach's Chaconne (which I adore -

it's just not made for train decor.)

The artist who ignores his context,

no matter if the talent's great,

is failing to communicate.

I hope that we can count upon, next

commute, a savvier setlist.

Then maybe beauty won't go missed.

I know he also played a little Ave Maria, etc., but I agree with Elaine Fine that the music wasn't very well-chosen for the venue. (She says everything I wanted to say, and quite eloquently, so sonnets were all I had left. Sorry.) The Chaconne, which I count among my 4 or 5 favorite pieces of music ever, is an almost unbearably intense piece that is best heard with rapt attention paid to it's inexorable logic. If I happened to wander in on that scene from the top of an escalator, I'd certainly have stopped to listen, if only because I would've recognized Bell and been intrigued by the situation. I suspect, given the way crowds work, that if three or four such people had stopped to listen, their presence would have attracted more and it could've become a scene, but I'm not at all surprised it worked out as it did. However, if I didn't know the music, I suspect I would've found the playing a little much for that setting.

In fact, the couple of times I've heard Bell live, I've found his hyperintense mannerisms to be somewhat distracting - I can easily imagine that created a barrier for some who walked by. It's not the kind of playing that fades into the steelwork. I'm sure the quality of my laptop speakers is part of the problem, but when I first fired up one of the sample videos, my immediate reaction was that the sound was awfully strident for what I'd want to hear walking to the train - and I love this music and Joshua Bell's playing. Now I can't explain why Jeremy Denk didn't draw bigger crowds, but I can tell you I knew a post like this was coming.

Monday, April 9, 2007

To Infinity, and Beyond!

One of the Dial M for Musicology guys recently asked for suggestions of good music appreciation tools for the grown-up non-student. He mentions the Bernstein Young People's Concert DVDs which, at their best, are fantastic and definitely not just for young people. As it happens, I'd recently been thinking about one of my favorite Bernstein lectures, "The Infinite Variety of Music." (Let's call it TIVOM, to save time.) This talk was originally given on a TV show, Omnibus, the likes of which would be inconceivable on network TV today. I first read the transcript in a book, also called The Infinite Variety of Music. Like The Joy of Music, this book is a loose assemblage of television scripts, imaginary conversations, essays, etc. Both books made an enormous impression on me when I was falling for music, and I especially remember being blown away by the revelations of the TIVOM transcript.

In a way, it's kind of embarrassing now because I understand better the tricks that Lenny had up his sleeve, but I still think it's wonderfully done and it shows him at his inspirational best. His basic device is to take a simple four-note melodic pattern and show how many different famous melodies have been spun from it. (The fun-with-themes starts about 9 minutes in.) It's not accidental that the sol-do-re-mi pattern he chose is such a classic tonal formula, but the fun is to see how different the notes can sound according to context. I had been thinking of this lecture because of my recent posts (here and here) about the wonders of pedal point, a very basic and often-used compositional technique that remains surprisingly fresh.

It's interesting and instructive that he doesn't choose to do vocabulary lessons on terms such as tonic, dominant, and triadic, but keeps the focus on the musical selections he's chosen. When I got my set of Young People's Concerts DVD's, one of the first I sampled was on Concertos, and I found it surprisingly dry, partially because that lecture spent a lot of time defining words like concertino and theorbo. It felt more like a history lesson than TIVOM does. Bernstein is at his best when his passion for the music is at the fore. My own feeling about music appreciation is that encouraging such a passionate connection with the music is by far most important; once it's established, the student will be much more motivated to seek out helpful terminology and historical details.

A few years after first reading TIVOM, I managed to get a boxed set of Bernstein LPs that had the TIVOM lecture on a special extra disc. (Reading the transcripts was always a challenge since they are full of musical examples.) I can't seem to find this audio (or better yet, the original video) anywhere else, so I've posted it myself. I also added stills for most of the musical examples from the book. These were hastily created in Finale, and I'm sure there are little mistakes here and there. They don't make for the most scintillating visuals, but I decided against the PBS documentary technique of overlaying a bunch of Bernstein-in-action stills. That always creeps me out, all those slow zooms in on a person frozen in motion. As in the book, the examples are all notated in C to make comparisons easier. At some point I may try to improve these annotations, but that would take exponentially more time than I've already invested, so for now I post as is. Enjoy!

Saturday, April 7, 2007

What's it all about?

I know I'm strawman-ing poor Mr. Teachout here, but I'm intrigued by the suggestion that the recording is somehow more 'real and reliable' than the memory of the live experience. Of course I understand what he means, but this reveals again the tendency, especially among reviewers, to want to talk about musical performance in objective terms. "The heat of the moment" apparently shouldn't be allowed to fool us, to cloud our judgment of the true, objective quality of a performance. And yet, the heat of the moment is what it's all about. No doubt, the development of a recording industry has changed this dynamic to some degree, as I noted here, but I continue to hope that classical music is still most at home in a live context where the heat of the moment means anything can happen. It's fine to comment on how well a live performance translates to a disc that will be heard over and over again, but that's something different than what the performance means in the moment.

This is one of the bittersweet things about our art: a beautiful moment is gone as soon as it appears, living only in our memory of it, no matter how heated that memory is. This creates a special kind of conflict in the directionally-oriented structures of Western music. The music tells us we're going forward towards something, but our minds may get stuck in particular moments that have already passed. About a month ago I heard the extraordinary young violinist Stefan Jackiw play the Beethoven Violin Concerto. (I don't mind admitting that I know Stefan, so I won't pretend to be objective, although there's a pretty broad consensus that he's got it all.) There's nothing remotely self-indulgent about his playing, which is ideally suited to that piece, but I still found myself distracted from the music by the unfailingly astounding fiddling - the beauty of tone, perfection of intonation, the naturalness of phrasing, etc. The very fact that Stefan manages to play in a way that serves the music was distracting because it was so successful at not being distracting. OK, perhaps I'm just revealing more of my A.D.D. tendencies here, but I think this illustrates something about how the heat of the moment works.

I like what musicologist Phil Ford says here about the tendency for musicologists to focus much more energy on how performers should perform (performance practice studies) rather than on how they actually do perform. Because musical notation can provide so much information (certainly the typical score gives more prescriptive information than the text of a play or the choreography for a ballet), the basic mindset is that the performer exists simply to translate a score into sound. I've already quoted this interview with Alfred Brendel in which he dismisses the notion that a performer could be called a genius when his/her task is simply to serve the genius of a composer. This ignores common experience: an essential part of the communicative power of music has to do with the physical act of performing - not to mention the live acoustic, the shared interaction with others in the audience, the heat of the moment, etc. I wouldn't hesitate to say that Stefan's genius was as vivid to me in that concert as was Beethoven's - even Stradivarius's genius was on display. It's not just about Ludwig.

[Here's something interesting: I had just remembered a post from Elaine Fine's blog in which she talked about a non-professional acquaintance being more focused on a soloist (Vadim Repin) than the composer (Shostakovich). I went to fetch the link and discovered that Fine titled that post "What's it all about?" I'd already chosen the same title for my post, so I'm keeping it, but it's something I love about the interconnectedness of the blogosphere.]

The third recent article that inspired this post was a NY Times feature on the explosive infusion of talent from mainland China into the classical world. What I found compelling was how unapologetically these non-Westerners embrace the very Western classical tradition. At a time when a postmodern mindset has us questioning both long-held assumptions of cultural superiority and our overemphasis on music of dead composers, the Chinese pianist featured in the accompanying video plays Rachmaninoff as if his life depended on it and with no sense that this is music our wiser heads like to pooh-pooh as hopelessly unprogressive. I tried to tackle that progressive problem in this post past, but it's a sticky one. Should we give more attention to music that moves the art forward, or is the music itself all that matters? Well, it's an unanswerable question, but it's refreshing to see these students who don't seem to care about that - they play Rachmaninoff because it deserves to be played and Amen to that. They may play Schoenberg with the same passion and dedication, but I wonder. (Let me apologize now for generalizing so gliby about a pretty large group of people.)

I miss the time when I felt the same way. When I was listening to good 'ol Rachy 2 recently, I had to fight off those inner voices that kept saying, "that's just another big, sappy tune - nothing interesting or challenging about it. What a panderer, that Sergei!" I'm happy to say that the inner voices lose out, but the price of musical training is often that we learn how not to like things we used to like. The problem is well-summarized by Teachout here:

Is it possible for a critic to know too much? Not a chance. The unhappy truth is that it’s far more common for us not to know nearly enough about the art forms we review. (If you doubt it, ask any artist.) But I’ve also discovered that the accumulation of knowledge can inhibit our ability to appreciate an artistic experience. I know middle-aged opera buffs who never seem to enjoy the performances they attend. Whenever they go to “La Traviata,” they always end up spending the whole intermission grousing about how the soprano wasn’t as good as some half-forgotten diva they heard in Milan 37 years ago. They’ve lost the knack of enjoying the performances they’re seeing—not to mention the piercing beauty of the music they’re hearing….

The more you learn about an art form, the harder it becomes to enjoy it in a straightforward, uncomplicated way. The literary critic R.P. Blackmur had this phenomenon in mind when he observed that “knowledge itself is a fall from the paradise of undifferentiated sensation.” Go to “Swan Lake” for the first time and you’ll be blown away by the flood of gorgeous new sights and sounds that spills over you. Go 20 times and you’re more likely to notice that the orchestra played out of tune and the ballerina did 31 fouettés instead of 32.

That’s not snobbishness. It’s connoisseurship, and it’s a good thing—unless it gets between you and the immediate experience of art. Gratuitous pickiness is a soul-killing trap against which the critic must always be on guard….

Snobbishness. Connoisseurship that slides into Elitism. That's not what it should be all about, but it's a hard path to resist. The mighty Soho the Dog complained last month about a Boston classical radio station fan poll that, not surprisingly, had a lot more Rachmaninoff than Schoenberg (none)- and no music by living composers. The comments to his post included the predictable Pachelbel bashing and other quotes such as this: "Meditation from Thais? I'd be very, very ashamed in Boston right now." Coincidentally, I was listening to a recording of Stefan Jackiw (at age 15) playing the Meditation this morning (hear here) and I can't think of any melody more perfect, especially as thus played. (The Paganini on that recording ain't bad either.) What's it all about? Stefan meditating is definitely part of the answer.

Friday, April 6, 2007

Pedal Tone Junkie

As I was demonstrating from the piano, I suddenly saw yet again that the trusty old pedal tone technique was hard at work in a beloved spot. I wrote awhile back about how often I've unkowingly fallen for this device. In that post, I discussed some more typical uses of the pedal point trick in which the sustained bass note creates tension that resolves with a big arrival. (Examples from Mendelssohn's Octet here and here; from Tchaikovsky's 1st Piano Concerto here.) In the Figaro quartet, the pedal tones function more to provide repose in the midst of all the madcap goings-on.

Again, it's worth noting that there's nothing fancy or complicated about this technique, e

specially as used here. The melodic phrase that Figaro introduces over the pedal is about as simple as can be, and then it's repeated in harmony with the ladies. Pedal points generally create tension because they're dissonant with what passes above, but there's not much of that here. The effect has as much to do with the contrast it provides in context. These are basically silly characters and ridiculous situations, but for a brief time Mozart makes us see them as genuine and non-conniving - at least the Countess, Susanna, and Figaro. Basically, the pedal persists through three short versions of this phrase; its conjunct, sustained qualities make the pedal seem more static than suspenseful.

specially as used here. The melodic phrase that Figaro introduces over the pedal is about as simple as can be, and then it's repeated in harmony with the ladies. Pedal points generally create tension because they're dissonant with what passes above, but there's not much of that here. The effect has as much to do with the contrast it provides in context. These are basically silly characters and ridiculous situations, but for a brief time Mozart makes us see them as genuine and non-conniving - at least the Countess, Susanna, and Figaro. Basically, the pedal persists through three short versions of this phrase; its conjunct, sustained qualities make the pedal seem more static than suspenseful.The Count, who won't really sing an honest note until the equally stunning conclusion of the Act IV finale, doesn't participate the first time we hear this tune. He follows up by barking at Figaro a bit more and we get a more typically intensifying pedal tone situation as the women implore Figaro to stop pretending. Figaro's reply leads into the climax of the quartet as all four participate in the innocent tune shown above, again with a time-stops-for-beauty pedal holding things together. Of course, the Count is fretting about when Marcellina will arrive to put her claim in on Figaro, but the effect is still an all-too-short bit of sublimity in the middle of the ridiculous; the crazed entrance of the gardener sends things hurtling back into confusion.

You can hear this brief excerpt and watch the score go by, with pedal tones highlighted, here.

As is so often the case with works of genius, we find it's often less the sophistication of the materials than how they're assembled. I thought of that this week both in teaching Beethoven's 5th symphony and listening (via CD) to Maurizio Pollini scorch his way through Stravinsky's Trois mouvements de Petrouchka. For all the biting rhythms, polytonality, and complicated textures, the primitive Russian folk-tunes are what hold that music together. A lesson for the kids out there.

Thanks a lot, Carl

However, I've been doing less music listening lately (mainly because I'm too lazy to pick out CDs for the commutes) and have been trying to do the NPR thing. It's usually a pretty safe haven from sports, and when the local news folks come on, the announcer first says, "In sports . . ." at a predictable enough time that I can click the radio off for the 20 or so seconds they devote to such stories. I'd never heard Carl Kasell ,the basso Morning Edition newsreader, say anything about sports, but wouldn't you know that on Tuesday morning he led with an immediate reveal of which team had won it all? (I'll keep the winner anonymous for any of you on the same Lenten journey as me.) Done in by Carl Kasell! I suppose the lesson is that I wasn't really supposed to be enjoying 'giving something up' anyway, so it was probably poetic justice. (A look at the profile linked above reveals that the mysterious Mr. Kasell is fan of UNC basketball. Who knew?)

With the Red Sox in the midst of their opening week, it's required some real skill to avoid those stories, but so far, so good. Haven't figured out yet how much sports to let back into my life going forward. I'm pretty sure that the cold turkey thing is probably easier than trying to ease back in - once you start paying a little attention, the wandering eye is quickly attracted to this story and that and suddenly you're reading the sports section with your hair on fire. One thing I know - if I ever find myself reading NASCAR stories, I'm getting back on the wagon. And if Carl Kasell starts delivering NASCAR news, I'll know the endtimes are near.

Wednesday, April 4, 2007

Sunday, April 1, 2007

Constraining Monroe

Opera buffa for our time?

About a week ago, Soho the Dog posted an odd little open-ended quiz for the classical blog community. I never tried to complete it because I found the opening question to be too much of a stumper: "Name an opera you love for the libretto, even though you don't particularly like the music." It felt like a 'separate the men from the boys' question since it takes a good bit of investment in opera to get to know a libretto well when you don't even like the music. I ended up feeling more boy than man because I simply couldn't think of any libretti that I truly loved - probably The Marriage of Figaro and Albert Herring would top the list, but I love those libretti because of the music.

However, it occurred to me during last week's run of opera scenes that the selection we performed from Haydn's La Canterina came as close as anything to fitting the bill. I'm on record as saying I'm not much of a fan of Papa Haydn, so I was surprised at how much I enjoyed this scene. On reflection, I don't think the music had a lot to do with it; all the funniest bits were in the recitative and it was some pretty perfunctory recitative from a musical point-of-view. The quartet that concluded the scene was fine but very much by-the-numbers. I wouldn't say I love the libretto, so it doesn't really fit Soho's question, but the zaniness of the story is what makes the opera tick. The music is almost an afterthought.

Speaking of zany, I return to my question about why contemporary composers aren't more interested in musical theater or comic opera. An entertaining story that carries an audience along and features lots of silly highjinks might make listeners more receptive to music that's new. Since I can't imagine that I'd ever be in a position to carry out this idea, I'm going to reveal a great possible comic opera property: The Seven Year Itch. Watching this movie again reminded me how stage-y it is; it also has a pretty simple, even flimsy plot, which is more about amusing situations and characters than building a rich narrative. That's comic opera material, all right. All of Richard Sherman's little monologues could make for some wonderful arias and a clever composer would incorporate Rachmaninoff's 2nd Piano Concerto into the score. I suppose it would also work well as a more traditional Broadway musical, but that's too easy.

Speaking of comedy, my recent update about George Benjamin and constraints led me to this very interesting interview with Benjamin and a younger composer, Luke Bedford. About his influences, Bedford says:

I'm still most inspired by the music of the 50s and 60s, people like Stockhausen, Xenakis, and Boulez. But I'm also fascinated by comedy. I find I can learn things technically from shows like Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Benjamin says of his admiration for another TV comedy:

In the beginning of a Fawlty Towers episode, reality is disturbed. You get about five different types of character, and they all send out their tendrils, and by the end of half an hour, they're all connected in the climax in the most atrocious ways. It's a mix of inevitability and awful, agonising surprise: and that really is a lesson in composition. You set up things that disturb normality in the beginning; by the end it's culminated in something surprising. It's as if in bar five of a piece, you plant a tiny little detail which shouldn't be there, and that little moment grows into the biggest element in the music 10 minutes later.

I like these quotes because they reveal a respect for the craftsmanship that goes into the best TV shows. I was never the biggest fan of Frasier during its run, mainly because I find the three main supporting characters (Martin, Roz, Daphne) to be poorly written and acted. (Frasier and Niles are perfect characters, of course.) However, watching it every now and then in syndication, I marvel at how beautifully the best episodes are constructed. Silly yes, but undergirded by a skillfulness that would make Rossini or Donizetti proud - I think even the fugal-minded Bach could appreciate the clockwork-like intricacy of these plots. So, rather than another overblown, self-important and depressing story, why shouldn't the next big opera commission bring Marilyn Monroe to the Met? I can just hear a coloratura singing, "He'll never know because I stay kissing sweet the new Dazzledent way."