I was recently researching various musical settings of William Blake's poem The Lamb. One of my favorites is by the great American song composer Lee Hoiby, and I came across this recording of Hoiby himself accompanying the song.

It's a fine recording of a song which is successful in part because of its simplicity and directness, but there's something un-simple right at the start. Having accompanied and coached this song many times, I know well that Hoiby has laid a subtle trap for the singer (and pianist) in the one-bar piano introduction. As you can see below in bar 2, the left hand is syncopated one sixteenth note off from the right hand melody and vocal line, but Hoiby chose to begin the song with that left hand figure syncopated against...well, against nothing. Or, more specifically, against some unheard downbeat felt by the pianist and perhaps by the singer - but inaudible. So, if the notation is followed precisely, it will likely sound like the singer comes in early. We hear four eighth notes (suggesting something steady) but the voice enters halfway through the final one.

The curious thing about the recording above - with the composer at the piano - is that the singer basically comes in after four full eighth notes as if it had been notated this way:

When I see something like this with a missing downbeat, it somehow communicates that the music should be a bit off the ground. It suggests a floating sensation which probably means my wrists will come up as the fingers go down. This is as opposed to a grounded sensation in which I'd let my arm weight sink into the keys more. What difference does that make? Well, pianists have been arguing for ages about how touch and weight affect sound, and I don't want to get into the physics of whether any variable other than velocity is in play. But I do think the imagination of this floating sensation can have an effect on how the music comes out...somehow.

It's possible Hoiby also wants a sense that the sound doesn't really have a strong beginning; we're just tuning into a figure which has been going on imperceptibly until it sneaks in pianissimo. Unfortunately, Hoiby's performance, at least as it comes across in recording, doesn't quite fulfill that ideal as the low E-flat is actually quite rich and present. This recording, also featuring the composer at the piano, achieves this gently tuning in effect a bit better, though in this case I hear Hoiby's rhythm as closer to this (it's an important reality that performances of clearly notated music won't and shouldn't always come out mathematically precise):

I also couldn't resist doing a little audioshopping of the first Hoiby recording posted above. Here, I've compressed the space (by about a sixteenth) right before the singer enters, and I prefer it to Hoiby's unaltered performance. So for all my speculation about Hoiby wanting something less literal than he wrote, I still want something less pedestrian than what he settled on. I wonder if he simply found that the ideal of an imagined downbeat works better for the performer than the listener.

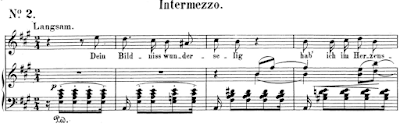

Of course I'm always interested in the connections this kind of situation sparks in my memory. In this case, as I thought about the notation, I had a strong sense I'd experienced a similar rhythmic challenge in another well-known art song. I kept thinking it was probably something by Schumann because...well, because that was my intuition and I know that Schumann loved to write in suggestive ways. But I also wondered if I was remembering something by Fauré or Debussy. It took a good night's sleep and a good hour's more thinking about it before I finally remembered the opening to this little song from Schumann's Op. 39 Liederkreis:

You may hear it sung here. I would not say this is one of my favorite Schumann songs, but there's no missing that suspended gesture in the very short intro. I'm sure my mind made this Hoiby → Schumann association because coaching a singer to find the downbeat in one is closely analogous to the other. The Schumann intro is ultimately easier and more natural both because 1) the notes aren't jumping around and 2) coming in on an upbeat doesn't feel quite so off-kilter as the out-of-the-blue downbeat in Hoiby. (The Schumann has still bewildered more than a few students.) Hoiby's choice to begin with such a low note also makes it sound more like a downbeat to begin with than Schumann's mid-range, second inversion harmonies. But I can't help wonder if Hoiby had Schumann's accompaniment in mind (consciously or not) and if he hoped to achieve a similar effect.

As a sort of postscript, I'll mention one other song which came to mind when I was doing a mental search for what turned out to be Schumann. The opening of Hugo Wolf's Ich hab' in Penna has confused many singers-in-training for similar reasons as Schumann and Hoiby, though it is quite different in character. Here, the frantic piano part begins with constant eighth notes starting on the "and of 1" and the singer should begin on the "and of 1" in the next bar. Though this isn't really a syncopation because there's no rhythmic stress on an offbeat, the absence of an initial downbeat helps propel the song's headlong energy. However, some singers can't help but hear the first note as a downbeat (even when the pianist tries to put a subtle accent on beat 3) so this misleads them into starting one eighth note too late. It's not so hard for the prepared pianist to right the ship but that makes for an uncomfortable mental gear shift! Hear here. (No pianist needs the stress of an unsettled start knowing that terrifying postlude is just around the corner.)